In May 2019, BTS played their mega-hit “Boy With Luv” on Colbert, channeling The Beatles’ first Ed Sullivan performance 55 years earlier. Complete with matching suits, a retro backdrop, a black-and-white telecast, screaming fans (something you don’t hear often on late night TV) and a drum kit emblazoned with “BTS” in The Beatles’ signature font, their debut on that hallowed stage was America’s major introduction to the K-pop group, similar to when John, Paul, George and Ringo did the same decades before.

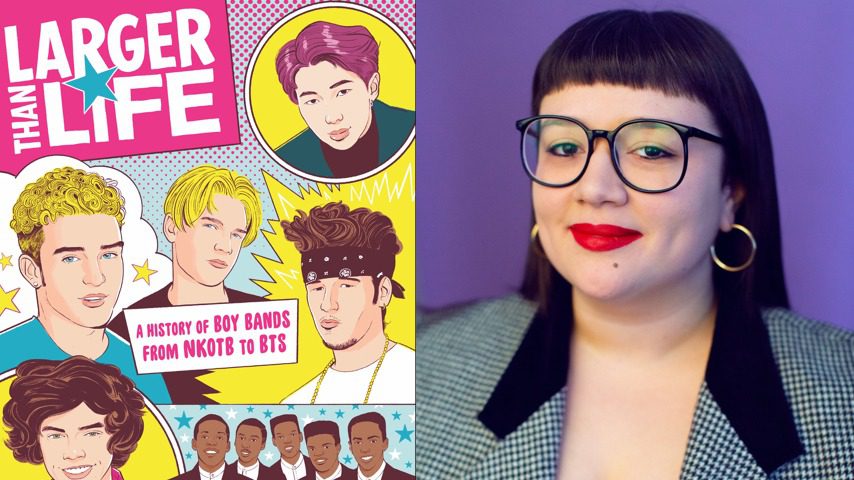

Maria Sherman’s new book, Larger Than Life: A History of Boy Bands from NKOTB to BTS, details the connection between The Beatles and BTS and every other boy band in between (yes, The Beatles were a boy band—get over it). “Boy With Luv” sounds nothing like “I Want to Hold Your Hand,” but there’s a clear lineage between the two, a timeline that includes early innovators like Menudo and New Edition and industry-altering stars like New Kids On The Block, Backstreet Boys and *NSYNC, all the way through modern iterations of the formula like the Jonas Brothers, One Direction, Big Bang and even BROCKHAMPTON.

Complete with detailed looks at each group’s fashion choices, purported rivalries, hair, fan fiction, girlfriends, conspiracies and—above all—their hits, Sherman strikes a perfect tone between cultural critic and super-fan, simultaneously applying gender theory and jokes that’d land at a comedy club. The book, with illustrations inspired by Tiger Beat, is a celebration of pop music’s most euphoric, life-affirming songs and the well-defined personalities behind them. It’s shockingly the first definitive history of the boy band genre itself. We recently caught up with Sherman to talk about the oft-forgotten boy bands of the past (justice for BBMak!) and a potential critical reevaluation of pop music’s best-selling groups of all time.

Paste: What gave you the idea for this book?

Sherman: I knew that I always wanted to write a boy band book, maybe around the time of One Direction’s dissolution, because it was like, “OK, I’m a little bit out of it and maybe now I can think more critically about it.” Though I do think you can be an eccentric fan and also be critically minded about what the experience is. K-pop fans sure know how to navigate that line really well. It just seems kind of absurd that this book didn’t already happen. I’m happy I was able to do it.

I wanted to talk about how poptimism, the idea that pop music deserves to be on the same critical plane as any other genre. Do you think boy bands will be more accepted in poptimist circles going forward?

I hope that’s where it goes next. It’s interesting because poptimism, I guess the idea of it, shouldn’t really be celebrated, but just treating any music with intellectual curiosity despite where it comes from, or considering where it comes from, rather, is pretty important and interesting. I think boy bands are removed from that conversation because they don’t write their own songs, and that’s sort of the tentpole of authenticity, which is a very sort of rockism idea that the most authentic you can be is if you’re writing the song. People treat music journalism that way where we’re very interested in the song composition. It’s interesting to see BTS become something that people are interrogating a little bit more, but I think that a lot of that is because their fans are so mobilized and there’s this digital audience that it’s kind of unavoidable. You’re going to interact with BTS in some capacity if you’re a person online. And maybe that’s reinforcing the idea. But I think boy bands are worth interrogation because a lot of the extra-musical stuff. Obviously the music is a big part of it, but why is it constructed? It’s constructed to illicit joy. It’s constructed to exist for a certain population or demographics of people, and why isn’t that worth interrogating, that phenomenon in and of itself? I’m optimistic that people will also be critical and give boy bands the same kind of intellectual curiosity that they’ve given rock and the Ariana Grandes of the world and hip-hop of the last couple of decades. I’m not sure it’s going to happen though. It’ll take some time.

“Why is it constructed? It’s constructed to illicit joy. It’s constructed to exist for a certain population or demographics of people, and why isn’t that worth interrogating, that phenomenon in and of itself?

In the book, you talk about misogyny and people discounting teenage girls’ tastes in music. How can we as writers and critics start listening more to that demographic?

I think by just paying attention to what they’re doing. I have whole Twitter lists dedicated to different fan accounts, and it’s really interesting to see how the language changes or even the artists they’re interested in. I don’t think I mentioned this in the book, but there was this phenomenon, I guess when I started thinking about boy bands critically in the 2015-2016 zone, when I was following a bunch of 5 Seconds of Summer accounts and then overnight they became BTS accounts, or it felt that way. You could follow these shifts and interrogate them critically, all giving legitimacy to what they mean for young women and young queer youth and all of these populations. I also think maybe remembering that the music tethered to adolescence or associated with adolescence informs musical taste in the rest of your life. I think there’s some fact out there that when you hit 30 or your mid-20s, most people sort of stop their music discovery hunt. If we’re ignoring this huge chunk of time because it’s silly or embarrassing to return to, we’re depressing our value systems for music to a very niche amount of time in people’s journeys of musical discovery.

Seeing K-pop stans mobilizing to affect positive political change has been a seemingly different trend, but I think you argue that they’ve always been political anyways.

In the One Direction days, you’d just be excited if Harry Styles picked up the rainbow flag that a fan threw onstage. Now in the K-pop era of boy band fandom and pop music fandom in general, it’s not enough to just signify support for Black Lives Matter. [K-pop stans] really put pressure on their idols to take action, which is why we see things like BTS donating $1 million to Black Lives Matter a week after fans had shut down all these racist police apps. Any pop music fan, especially boy bands because that’s a music that’s so tethered to identity for a lot of people, they want their boy bands or they want their celebrity whoever-they-look-up-to to reflect their value systems. Today I think people are especially politically engaged and they really demand and require that the boy band reflects those ideas.

Larger Than Life: A History of Boy Bands from NKOTB to BTS Cover Art:

What was it like going back to music from your childhood?

I think the part that felt most nostalgic was listening to Millennium and No Strings Attached in full because obviously the singles still exist—if you’re going to go to karaoke, you’re going to hear it. Certain touchstones still exist, and I think that speaks to the popularity of this and why this book should have existed, but some of those songs are such filler. It’s sort of incredible how they really should have spent more time on this. It was sort of astonishing to me how many of these songs were just like Boyz II Men rip offs or straight beats ripped from early hip-hop or R&B. How much of this Backstreet Boys and *NSYNC era comes from Black music? I wasn’t thinking about pop music in racialized terms where the source material came from at the time. It is really interesting to hear K-pop fans interrogate that more because they have the access to that knowledge. That’s been really interesting to see because I definitely never thought, “Where are they getting this?” I just thought they had a special gift from above and everything they did was unique or innovative and meant for me and other young people. I think that’s been the biggest thing: A lot of these B-sides suck because they’re trying to be something they’re so clearly not.

Modern fan bases are way more cognizant of racial undertones, but as a former Backstreet Boys fan, I never thought about it.

All that pop music came about from a time when we really weren’t interrogating where music was coming from in the same way. It’s not just that K-pop fans are more politically progressive—though I would argue that of course they are—I think there’s also something to be said about the fact that the groups of their affection are boys of color in the way that boy bands in the Y2K really weren’t.

Larger Than Life: A History of Boy Bands from NKOTB to BTS is out now, and you can order it right here.

Steven Edelstone is the former album reviews editor at Paste and has written for the New York Times, Rolling Stone, the Village Voice and more. All he wants is to get a shot and beer combo once this all blows over. You can follow him on Twitter.