Lana Del Rey’s creative vision has always been dangerously insular. Musicians are known for their abilities to tell stories, and Del Rey has demonstrated an affinity for making hers as dramatic as possible. Her 2012 breakthrough sophomore album, Born To Die, placed the singer directly in front of the sweltering and unrelenting spotlight where the artist’s authenticity was torn asunder. She was pioneering this moody, billowy pop sound, yet her Lolita persona stood at the epicenter of the hype. Figuring out who Del Rey is—as primarily shown through her discography—can be as mystifying as the songs themselves.

2014’s Ultraviolence was a critically acclaimed project, while Lust for Life basked in being a phantasmagoric thrill ride soaked in lush soundscapes. By the time 2019’s Norman Fucking Rockwell! rolled around, fans and critics alike were finally able to really unpack Del Rey’s complexities. She longs for never-ending love, complete with permanently plastered-on smiles and white picket fences, yet this seems to be her only objective. While some deemed her “anti-feminist” for depicting abusive relationships as inconsequential lyrical fodder, she merely conveyed the way our world normalizes them.

Del Rey’s biggest offense is self-indulgence: If something doesn’t revolve around her entirely and favorably, it’s an inconvenience to her. We saw it two years ago when she waved her self-righteous fury at critic Ann Powers for not heralding Norman Fucking Rockwell! as the masterpiece Del Rey believed it to be. She did it again just last year, stepping up on her Instagram soapbox to throw female music artists—most of whom were women of color—under the bus:

Now that Doja Cat, Ariana, Camila, Cardi B, Kehlani and Nicki Minaj and Beyoncé have had number ones with songs about being sexy, wearing no clothes, fucking, cheating, etc — can I please go back to singing about being embodied, feeling beautiful by being in love even if the relationship is not perfect, or dancing for money — or whatever I want — without being crucified or saying that I’m glamorizing abuse?

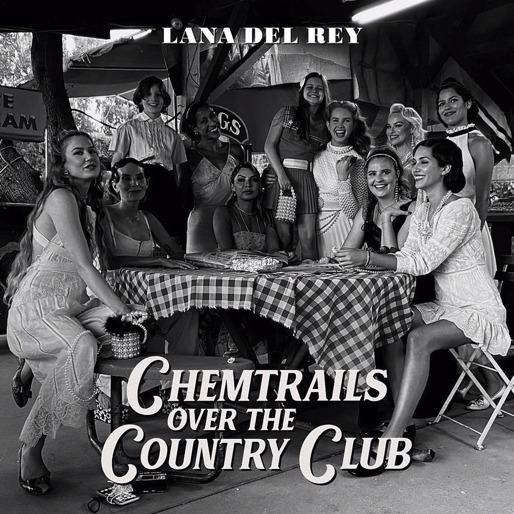

The backlash to the (since-deleted) post was swift and fierce, with Del Rey responding that she selected those artists as examples because they were her “favorite fucking people.” This instance reiterated just how vainglorious she could be, and with the release of Chemtrails Over the Country Club, the focus is placed back to the limitations of her universe. This is when the singer is begrudgingly at her best, as she spins tales of heartbreak, misfortune and loneliness. This is one of the most cohesive albums she’s released in years.

The soft piano chords that envelop “White Dress” are enchanting and serve as the perfect sonic backdrop to syrupy, hushed vocals telling a story of modest beginnings: “When I was a waitress wearing a tight dress handling the heat / I wasn’t famous, just listening to Kings of Leon to the beat / Like look at how I got this, look how I got this / Just singing in the street / Down at the Men in Music Business Conference / I felt free ‘cause I was only 19.” “Chemtrails Over the Country Club” is an elegy about disillusionment with suburbia, but is slightly underwhelming in its execution. Although title tracks are typically the icing on the cake, this one is particularly anticlimactic and begs for more inventiveness.

“Tulsa Jesus Freak” is a sultry reprieve on Chemtrails Over the Country Club, with Del Rey’s echoey and sumptuous vocals reciting lines like, “Find your way back to my bed again / Sing me like a Bible hymn.” The slow buildup of “Let Me Love You Like a Woman” is endearing and strong. Del Rey gets lost in her own paranoia mixed with existentialism on “Dark But Just a Game,” insisting that “we keep changing all the time / The best ones lost their minds” over hypnotizing percussion and fluttering guitar. This sentiment continues on “Not All Who Wander Are Lost,” as she impressively showcases her vocal range for its chorus.

“Yosemite” is structurally and lyrically simplistic, but still manages to possess an intensity not heard on other songs; the singer’s somber caterwauling embodies the emotional dissonance from which she’s been trying to heal. “Dance Till We Die” is a hollow anthem of resolve, regardless of the damage done. Del Rey ends things with a tiresome ballad featuring Zella Day and Weyes Blood; “For Free” is beautifully arranged, but doesn’t do much to hold the listener’s attention. The wails are cumbersome and unwieldy, with notes that are held for far too long.

Chemtrails Over the Country Club is a record full of euphoric highs and baffling lows. It’s an enjoyable listen that cinematically celebrates Del Rey’s vocal prowess. But perhaps most importantly, it places her front and center as the scrappy protagonist no one expects to win. Victory is irrelevant, however, since she is exactly where she belongs.

Candace McDuffie is a culture writer whose work has appeared in outlets like Rolling Stone, MTV, NBC News, and Entertainment Weekly. You can follow her on Instagram @candace.mcduffie.