Over dinner at Junior’s, my boyfriend and I played a game where we tried to guess who else there was on their way to the Geese show—pretty much everyone under 30, we reasoned, with some doubt (Were the dozen lively, musical chairs-ing high schoolers giddy about seeing Geese live, or were they just celebrating a birthday or the closing night of their school play?). A meal at the old school Brooklyn diner, famous for its cheesecake and sky-high deli sandwiches, seemed like the perfect preamble for tonight’s show—the second of two sold-out nights at Brooklyn Paramount, the 2,700-cap venue across the street. Other than a set at Tyler The Creator’s Camp Flog Gnaw festival in Los Angeles later that weekend, the Brooklyn band’s homecoming shows would mark the end of the American leg of the Getting Killed tour.

This tour—and autumn of 2025 in general—saw Geese breach indie darling containment, breaking through to the mainstream in a way that indie rock bands rarely do in the 2020s. They’d already generated respectable buzz with their first two studio albums, 2021’s Projector and 2023’s 3D Country, but from the beginning of the rollout for the Kenneth Blume-produced Getting Killed, it was clear that the band was bracing for massive impact. It definitely helped that frontman Cameron Winter’s solo album, Heavy Metal, snuck in under the wire last December (a time of year often ignored by the music press) and became a critical sleeper hit. Getting Killed’s warbly and weirdly prescient single “Taxes” became the de facto left-of-the-dial song of the summer; Cameron Winter leaked its follow-up single, “Trinidad” on Instagram against his record label’s wishes, and the track’s blood-curdling chorus became a runaway meme. The day after Getting Killed dropped, the band played a pop-up show behind Brooklyn’s Lot Radio to an audience of about 4,000 people. On that September afternoon, pressed up against the metal barricade and the bodies of strangers sweating on concrete in the last gasps of summer, I watched from spitting distance as Geese became a generation-defining band in real time.

Since that album release show, Geesemania has reached epidemic proportions—the band played the return episode of Jimmy Kimmel Live! following the show’s brief cancellation; their song “Au Pays Du Cocaine” sparked a viral trend that had people dressing up as sailors in big green boats and big green coats; celebrities ranging from Cillian Murphy to Patti Smith came out as Geeseheads; Cameron Winter covered Bruce Springsteen’s “Dancing In The Dark” for an Xbox commercial. Before the second Brooklyn Paramount show, Mr. Met himself showed up to surprise the band backstage, and as I write this, I’ve just been informed that a snippet of “Cobra” played during NBC’s coverage of the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade while a balloon shaped like a weiner dog drifted down 34th street.

A week before Geese’s homecoming show, I went up to Woodstock on a rainy night to see the band perform at Levon Helm Studios—a venue fitting for Last Waltz Season but one that Geese and their rabid fanbase had clearly outgrown. Beneath its wooden rafters, Geese’s normally rowdy live show took on a campfire singalong subtlety. “Did y’all get in okay? I should’ve powdered my ass this morning,” Cameron Winter bantered with the audience—a rare over-30 crowd for a band that’s struck a surprising chord with teens and young adults. Lit by Edison bulbs, Geese played a stripped-back set of relative deep cuts, forgoing many of the high-energy singles that have made up the bulk of other shows on this tour. The restrained rendition of “Trinidad” that opened their set made the track even creepier, intensifying the blow when the band went full “THERE’S A BOMB IN MY CAR” at the final chorus. Surprise pulls from their pre-Getting Killed catalog, like “First World Warrior” and “Space Race” felt like Geese letting us in on a secret.

If the set at Levon Helm Studios was, to borrow Cameron Winter’s deadpanned lounge lizard description, “an intimate evening with Geese,” Geese’s Brooklyn Paramount set had the energy of a hometown house party on Blackout Wednesday. The weekend before Thanksgiving, Geese fans packed the Downtown Brooklyn ballroom to witness the homecoming of New York’s definitive Gen-Z rock band.

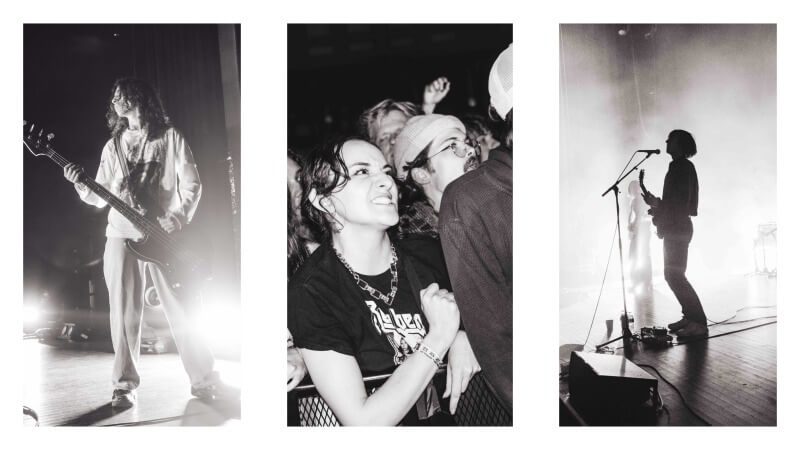

The young crowd milled about before the main event, chatting in-between (and annoyingly, sometimes over) moody opening sets from Michigan post-rock seven-piece Racing Mount Pleasant and Irish singer-songwriter Dove Ellis. Many attendees were rocking big green coats. A few crocheted geese hats bobbed above heads in GA. As our hometown headliners took the stage, the audience broke out into chants of “GEESE! GEESE! GEESE!” Ever the shrinking violet, Cameron Winter responded to their cheers with a sheepish, “Oh, pipe down,” which only riled them up more.

“Islands of Men” kicked off Geese’s set with looseness and ease—Dominic DiGesu hitting the bongos, Max Bassin tapping his sticks, Emily Green striking her strings as Winter walked over to her, the two of them mirroring one another for the track’s slow build. As in-sync as Geese are as a full band, it’s easy to single out star-making moments for each band member: the intricate jam on “Islands Of Men,” for instance, makes it clear that Emily Green is a generational guitarist and the one who’s truly orchestrating the song’s ebb and flow. Geese are, individually and as a unit, adept at the give-and-take that balances out a band, knowing when to fall back and when to step into the spotlight.

After warming up the crowd, Winter paced around the darkened stage in time with Green’s jagged, congested strumming, and hissed, “This next song’s about a lotta fuckin’ horses!” He muttered something else as his bandmates launched into “100 Horses,” but it was incomprehensible beneath Bassin’s drums crash-landing with a reckless, burly agility, an athletic and seemingly impossible feat of primality and precision. Cameron Winter’s emphatic ad-libbed “Yooooooooooo!” that ushered in Getting Killed felt like kicking down the doors to Geese’s homecoming rager.

Geese detoured into the 3D Country portion of their set, beginning with the 2023 record’s cold-open call-to-arms: “God of the sun, I’m takin’ you down on the inside!” Geese are known to throw cover jams into the breakdown of the “2122,” and tonight they excerpted The Stooges’ “Fun House” with some help from members of Racing Mount Pleasant on “horns and shit like that” (to use Winter’s exact phrasing). Following 3D Country’s raucous opening track, Winter melted his yowl to a croon for the psych-rock slow dance “I See Myself” before breezing through the tour debut of B-side “Killing My Borrowed Time.” When Winter screeched “New York City! / Underwater!” during live favorite “Cowboy Nudes,” the entire room lit up, shouting along with him.

Getting Killed dark horse “Bow Down” detonated with a propulsive fury. Seeing “Bow Down” live makes you realize that it’s one of the album’s most sneakily catchy songs, in large part thanks to DiGesu’s thick, tunneling basslines that serve as a layer of foundation atop which the rest of the band can lose their shit—Bassin’s militant snare hits, Green’s strobelike strumming, Winter self-flagellating like a tortured Muppet street preacher. The same audience that tossed themselves around with abject abandon in multiple overlapping mosh pits for “Bow Down” soon after swayed with their lighters in the air (not phone flashlights,lighters) to Getting Killed’s breakout breakup ballad, “Au Pays Du Cocaine.”

Geese officially closed the show (and the tour) with a rambunctious encore of “Trinidad” (which Winter referred to as a Waylon Jennings cover, dedicating it to the outlaw country legend), but the real bring-it-home moment was the ten-minute live rendition of Getting Killed closer “Long Island City Here I Come.” It started with a minute of solemn keyboard plinking from Winter, joined by a couple shakes of a tambourine and a few stray plucks of Green’s guitar strings, until rattling snares charged in like a train pulling up to the platform. Winter’s vocals were pensive, his opening statement,“Nobody knows where I’m going” tinged with doubt, the “Here I come” refrain rolling around like marbles across the song’s crescendo. Green’s guitar licks morphed from a flicker to a firecracker, the pattering of DiGesu’s bongos served as a skeletal prelude to Bassin’s unrelenting drumrolls and Winter hammering high notes like he wanted the keys to fall off, slowing momentarily for emphasis as Winter wailed, “So too shall I reach Long Island City one of these days!”

“Long Island City Here I Come” sees Winter contending with his own mortality and legacy, seeking guidance from historical and musical giants, his deference occasionally challenged by his ego—as is the case with any artist who dares to aspire to the greatness of their heroes. How else do you get the gall to refer to the God that Joan of Arc communed with as “you-know-who,” or to tell Buddy Holly “You were there the day the music died / and I’ll be there the day it dies again?” “Long Island City Here I Come” is about grappling with the fearsome and arrogant goal of having an impact that will outlive you, and the heavens-tall order that comes with it: creating something meaningful enough to transcend the self and make the often egotistical pursuit of art worth it in the so-called “grand scheme,” the boundaries of which are unknowable. You don’t get to decide what gets remembered. Winter sings that “A masterpiece belongs to the dead,” but to create something while you’re alive is to surrender control over the place it takes in a history that’ll continue without you. It’s also the only direct reference to Geese’s home city on Getting Killed; it comes at the very last track and it’s not even referring to a part of the city that any of them are from. Long Island City isn’t invoked literally, but as a stand-in for oblivion, for the parts of a person’s legacy that exist beyond their mortal imagination.

As a born-and-raised New Yorker myself, I hold New York bands to a weird standard. I have a sense of hometown pride that borders on chauvinism, which has me inclined to both root for New York musicians the way you’d root for a sports team and to hold them to a higher standard than their counterparts. For better or worse, growing up here spoils us. As a kid I couldn’t fully appreciate the novelty and impact of things like school trips to the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the New York Philharmonic. As I got older and started going to shows and ingratiating myself in the city’s punk and DIY scenes, I took for granted the sheer volume of storied New York music venues, the fact that I could count on all my favorite artists to come through my city when they went on tour, and that on any given night, great live music was never more than a few subway stops away. I grew up in the same neighborhood as some of the members of Geese, one whose name has become synonymous with artisanal markets and designer baby strollers. My parents—my mother a third-generation New Yorker who grew up in the Bronx and Washington Heights, my father a post-grad transplant from Detroit—had known a seedier version of the city. They’d seen New York fall into disrepair in the 70s and 80s, bore witness to housing and public health crises. They’d been to shows at CBGB’s and lived on streets populated by crackhouses and mafia fronts. By the time they had my siblings and I, they’d traded all this to battle it out for limited spots in one of Brooklyn’s best public school districts, their (and the city’s) more rough ’n tumble past existing only in stories.

The way the members of Geese talk about their New York upbringing in interviews feels similar to my own—growing up in a creative incubator, whether at school or at home, designed to root out raw talent and mold it from a young age. Beyond just the built-in cultural education city kids get and the resources afforded to us, there’s a major advantage to being raised by parents who value creative work and instill a sense of taste in their children. Because I was raised in a place that birthed so many significant movements and subcultures in the realms of art, music, and literature, and because I grew up in a family and an education system that instilled in me the belief that this city’s cultural and artistic history is a part of my history too, I’ve always felt a sense of obligation to live up to it all. It’s part of why I’m embarrassed by my own musical or literary blind spots, and why the pressure I put on New York artists to be exceptional is really just an extension of the pressure I put on myself. I recognize that there’s a more-than-healthy dose of projection going on here, and that white kids from Brownstone Brooklyn are not the be-all end-all arbiters of culture (nor should they be) but watching the payoff of four New York born-and-raised music nerds who’ve been honing their craft since they were children, spending their 10,000 hours learning the rules so they can bend, break, and rewrite them, feels like peering into the fully-realized ambition of the loud, brash, and ruthlessly competitive city that I love so fiercely.

I was raised on stories of the city’s Beat poets and punk prophets, by parents who worshiped at the altars of Lou Reed and Patti Smith, and when I was coming of age in an era of the city stirring from the aftershocks of a national catastrophe I was too young to fully remember, I turned to them and their turn-of-the-millennium successors to give my restless New York upbringing a language I could understand. I became an adult in this city, watched it shut down in the midst of a global pandemic and try to find its footing again. I moved away. I paid as many visits as I could. I moved back. I watched this city become a hub for pro-Palestinian and anti-ICE organizing, pushing back against a fascist regime led by a fellow native New Yorker, perhaps so fervent in its fight against him out of shame that he is one of our own. I watched as a population rightfully disillusioned by an old guard political establishment out of touch with the working people that keep this city running, regained enough optimism to elect a socialist mayor. Sometimes living in New York feels like living everywhere at once, having an up close and personal view of life itself, whether you want to or not. The greatest New York rock bands—from The New York Dolls to Suicide to Television to Talking Heads to TV On The Radio to the Yeah Yeah Yeahs—are ones whose work captures the city’s contradictions, its incessant aliveness. Watching Geese close out their tour with a triumphant homecoming show felt like watching them throw their arms around the city that raised them—a city that feels like an entire universe.

Grace Robins-Somerville is a writer from Brooklyn. Her work has appeared in Pitchfork, Stereogum, The Alternative, Merry-Go-Round Magazine, Post-Trash, Swim Into The Sound and her “mostly about music” newsletter, Our Band Could Be Your Wife.