Gaspard Augé believes in intention. Throughout the entirety of our conversation, he grabs at the small hanging threads of each question and unravels them until they are a tangled mess. Or maybe it’s a way to see what individual pieces create the larger fabric of why humans laugh, cry and dance. On the dance auteur’s debut solo album Escapades, out now, Augé weaves his own cloth, free of self-importance as he embarks on a new chapter.

Most people know of Augé through his work with seminal electronic duo Justice alongside Xavier de Rosnay. Their 2007 debut album Cross was a worldwide success, introducing global audiences to the maximalist magic found throughout their usage of hundreds of “microsamples” that fans are still deciphering to this day. They coined the term “opera-disco” as a way to make sense of their music, and it resonated as such. Even without many lyrics or vocals on most of their songs, the blown-out production evokes a sense of tragedy and drama, two things that made Justice some of dance music’s most beloved storytellers (and the soundtrack to my favorite anime music video).

Nearly 15 years removed from that genre-defining debut, Augé possesses a great deal of humility in the process of recording and releasing Escapades. “It’s a bit of a challenging move to go from a duo who achieved some kind of success,” Augé explains with a slight hesitation in his voice. “To go solo, you have to start from zero. Hopefully, people will listen to the record for that reason.”

It is also important to note that Augé is not a classically trained musician, and if you didn’t already know that, he will surely remind you. That doesn’t stop him from taking a more curatorial approach to music, in part inspired by stream-of-consciousness films such as Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, capturing sonic representations of emotions that cannot be controlled through a universal musical palette. He finds beauty in Italian library music (better known as stock music across the globe) and the vast sphere of emotions in classical compositions.

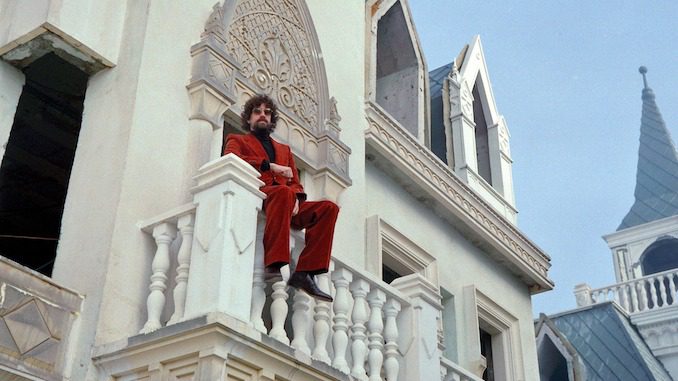

Escapades is an apt title for this reason, capturing fleeting moments of joy and excitement. Augé’s trademark maximalist production is much smoother on his solo release than his contributions to Justice’s ridiculously abrasive sound. The drama is still there, evocative of operas and ‘60s romance films, but without the cue cards to tell you what to feel and when. Even then, it feels unfair to pinpoint exactly where Augé’s mind went when creating this album, as it seems to write its own rules as it goes. That is where much of the magic in Escapades lies, allowing one’s psyche to fill in the blanks of choruses and hooks as subtle musical tricks transport listeners into his head. Despite sounding like a hyper-masculine display of skill and endurance on paper, it’s anything but. The surrealistic Filip Nilsson-directed visuals that accompany the album are oddly fitting, placing Augé on horseback, in deserts and in knight’s armor riding through barren kingdoms as the sole player in a world he’s trying to make sense of all the same as us.

In a world of superficiality and ego-driven displays of artistry, Augé simply asks for a few moments to be immersed in his compassionate sonic embrace. We could all use one of those.

Paste: To start off, people will definitely compare this to your previous work with Justice. Did you consider dispelling the expectations people may have when going into your solo debut?

Gaspard Augé: I didn’t put too much thought in the expectations of people […] It’s always a bit tricky because, obviously, people are going to compare what has been done with what there is now. It was a bit of a challenge to think about what kind of music could be seen as different from Justice. It’s always hard to reinvent yourself and that wasn’t the point of this record.

I guess it was more about getting away from the pop structure and getting rid of the ego and persona of vocalists. It’s not that I hate them, but it’s like reading a book. You’re making a movie in your head no matter how precise the description is. Then, most of the time you’re disappointed In the movie because it’s not what you had in mind. At some point, I got fed up with the room that vocalists can take in restraining your imagination.

Paste: Would you see instrumental music as a blank slate for listeners to impose their own beliefs onto?

Augé: There’s something more participative in instrumental music, because you are depending on your backstory. I find it more stimulating. I don’t know if it’s for everybody, but there’s no proper language. You don’t have to understand what the guy or girl is saying.

I feel that the mainstream world is obsessed with making the most efficient pop songs. I was happy to make music like that without that concern.

Paste: A lot of pop music has become very formulaic, precisely to hit those boxes as you mentioned. On the other hand, Escapades feels very intuitive to your artistry. Did you have an idea of structure for any track on this album?

Augé: It was made in a very organic way. Does that make sense? Most of the melodies came to me, not in dreams, but in those times where you hear something in your head that seems very relevant because your brain is making up all the arrangements. Then you record it on your phone and by the next morning, it doesn’t make sense anymore. I just kept the ones that still made sense when I woke up.

If you look at Michele Gondry or Fellini, you can feel that direct stream of consciousness that they are paying attention to. They pay attention to the things they don’t control that come to them in their sleep. For me, my main concern was to make something that was never abstract. This is not free jazz. This is not concrete music. It’s welcoming because it was made In a sincere way, almost a bit naive in a way that there is absolutely no cynicism.

I guess this is why I’m really attracted to the ‘60s and ‘70s with the utopian feel of music and that space age fascination. People were naively believing there could be a better place to live. I’m happy that happened because after disco and punk arrived, it really brought cynicism into music. For my project, I wanted to get close to this idea of naïveté.

Paste: Have you always wanted to take such a pure approach with your music?

Augé: Not really. I guess it’s a bit in the same approach in a sense that I’ve always been allergic to certain chords. I am not an academically trained musician and I can’t read a score or anything. However, there is an influence of what I know of classical music, but I’m not an elitist. To me, it’s the most emotional music you can listen to because it offers a wider spectrum of emotions that isn’t found in pop music. The musical spectrum has shrunk so much.

Take what you call “emo” in the U.S., it’s very cheap. It sounds like supermarket emotions. I’ve been struggling to never go the easy way when I’m trying to find a melody because I like to be touched and surprised. This is why I mostly listen to European composers and library music from Italy or Eastern Europe.

Paste: Do you think these criticisms you have are primarily present in American music?

Augé: There are tons of American composers I love, like Gershwin. It’s just that, especially with Justice, we always had this strong fantasy about the American dream and American way of life. This is what we’ve been fed when we were kids and teenagers. After a while, it seems that it’s very hard to find the local specificities and everyone knows what everyone is doing. It’s harder to find the edges of local sounds and you can’t avoid this worldwide “cool” act.

Paste: How does it feel seeing dance and electronic music rapidly changing from the early ‘00s dubstep craze to the revitalization of house?

Augé: We don’t know much about electronic music since it’s so vague. You take Aphex Twin and David Guetta, who are both in the electronic scene but they are making something so different. It’s hard to have an overview of what the music is.

For Justice, it was more about being punks in a sense that we wanted to make something aggressive and dynamic. Also, we didn’t know what we’re doing. Sound-wise and timing-wise, we knew, but again, we are not trained musicians or producers. We are just dialing it in. It was mostly about ignorance and wanting to try stuff and experiment with limited equipment. When I first started, we didn’t even have a computer!

Paste: It seems that you don’t even listen to a lot of electronic music, which would make sense since your influences show throughout your music as being more disco- and pop-aligned.

Augé: We grew up listening to rock and pop more than electronic music, so I guess it was a happy accident that we ended up in the scene. Even for us, the scene was already a thing for about 20 years so we didn’t exist in the political aspect of electronic music that was very militant where people had to fight and struggle to make that music exist. In 2005, it was definitely another story.

I still never listen to “clear” music, to be honest with you. Even the electronic stuff I listen to is more of library music that has been made by synthesizer pioneers such as Wendy Carlos and Suzanne Ciani. They were the first ones to have home studios and understand the potential of electronic music.

Paste: Do you feel like not being able to read music helps achieve this utopian vision you have with your music?

Augé: I guess I would lose that magic of finding something that works together like the melody. I hear when it’s right and when it’s not. I want to keep the magical thing of inspiration where I can write something that makes sense harmonically and musically. It still amazes me without knowing the tricks and craft of songwriting. It probably takes a bit longer compared to when you really know what you’re doing, but it doesn’t matter. If you can hear something and transpose it to something that people can listen to, it doesn’t matter if you can play the piano like a virtuoso.

Paste: It seems like you’re a film guy. How do they influence you?

Augé: Most of the time, I just really like the posters better than the movie itself. It’s the same dynamic as having lyrics in a sense that there’s more room for fantasy when just looking at a poster or record cover before you’ve seen an image or heard a note. I’ve bought so many records for the cover alone because it was something so appealing and mysterious.

I love soundtracks from the ‘60s and ‘70s because you have a strong theme that comes back throughout the movie, and it’s always arranged in a different way with the same notes. You can feel completely different moods depending on the arrangements, which is a trick we relied on. The narrative is not in the lyrics, but is created by the accidents and changes of mood throughout the track.

However, sometimes I watch a movie and it’s done in a way where you feel violated by the director. They clearly want you to feel sad, so they add sad strings or they want you to feel happy. Most movies I watch don’t have much music or music that isn’t too intrusive. It’s the same dynamic with vocals, where you have someone telling you how he feels and it gets between you and the music.

Paste: You seem to really value the overall experience of finding and listening to music, especially the intimacy that comes with intentional visuals and analog media.

Augé: I’ve always been collecting stuff and buying loads of books and records because I like the objects, as well as the experience of emotions you can get with just having the size of the image on a vinyl record. There’s not much you can project on a five-pixel image on your phone. Covers mean less now. Every record needs a cover but it’s not as significant as it was before.

Paste: The visuals for Escapades seem very intentional.

Augé: I’ve always been behind the intention of the art direction, and I worked with this director called Filip Nilsson. Aside from the fact that he’s a really talented director with a distinct style, the main bond we have is humor. He’s from Sweden and has this very Scandinavian, absurd and surrealistic way of seeing things.

I find most music videos today very self-indulgent and not genuine at all. There is something so fabricated that runs after what’s cool or what should be the next cool thing. It gets paralyzing when you start to think like that. To me, I just wanted to have something that fit the music without having to explain everything or have a theory. They’re more just small teasers for the tracks. It also is because of the way people consume music videos today, myself included, where we don’t even watch the full five minutes of a music video. Most people don’t watch more than one minute. It was about being realistic about what you can watch, especially when you’re scrolling on social media. We made them digestible, especially since five minutes of video can be restrictive.

Paste: What I gather is that you aren’t protective of these songs either, and you enjoy the meanings people project onto them, kinda like Nirvana.

Augé: I was a huge Nirvana fan. But, being a French guy with broken English, I never paid attention to the lyrics. I liked the attitude, I liked the music, but I completely skipped the message. What was great about Nirvana is that they weren’t aware of what was done in New York or Europe or Germany, because they didn’t have social media or magazines. I guess it’s a disappointment today that everyone knows what’s what and it becomes harder to create your own personal specificity.

Paste: It has become a lot more competitive so it takes a lot more for someone to want to invest time into listening to your album or reading an interview.

Augé: Making a 12-track album, I paid a lot of attention to the tracklist to make it coherent and to have some kind of narrative throughout the record, but I’m aware it’s a very old school way of doing things. You already know people are just going to pick their favorite track since that’s how music works today. I’m happy to have vinyl and the right kind of storyline made by the music. It’s a bit old school.

Paste: Speaking of old school, a lot of the influences found on the record are very personal to you in your growth as an artist and a person. Did you try to create an homage to these sounds?

Augé: I guess it was a big challenge to not try to make some kind of homage to this era. It’s not very relevant. We use a lot of analog stuff, but we also use a lot of plugins and digital tools. This is definitely not a statement of “Oh yeah, everything was better before,” because obviously it wasn’t. I wouldn’t be able to make the music if I just had access to a ‘70s studio.

It was interesting to mix those influences that I’m closer to from an emotional point of view with something modern, and then making it more exciting with self-sampling and using digital effects. At some point in some tracks, they were accidents that happened because of the computer. Those are sometimes the most interesting things.

We always worked in that aspect of never being purists about having to make a fully analog record, because it doesn’t really matter how you make it. We were kids in a toy shop, and we had access to great instruments. We can make a scene with anything. What was important for this record is to keep the freshness, the excitement and the playfulness of having limited time to work on these tracks.

It’s why I’m a huge fan of Mac DeMarco. His music is very serious in a sense that it’s so well-crafted and well-written with clever lyrics, and he’s effortlessly cool because he’s just himself. I see how serious music got because people are trying so hard to be cool. That’s tiring! We are just making music after all, we aren’t saving lives or working in a coal mine. People are just too obsessed with their image and how they’re going to be perceived.

I want to be playful. That’s so precious in the world of overinflated egos. It’s really rare.

Jade Gomez is Paste’s assistant music editor, dog mom, Southern rap aficionado and compound sentence enthusiast. She has no impulse control and will buy vinyl that she’s too afraid to play or stickers she will never stick.