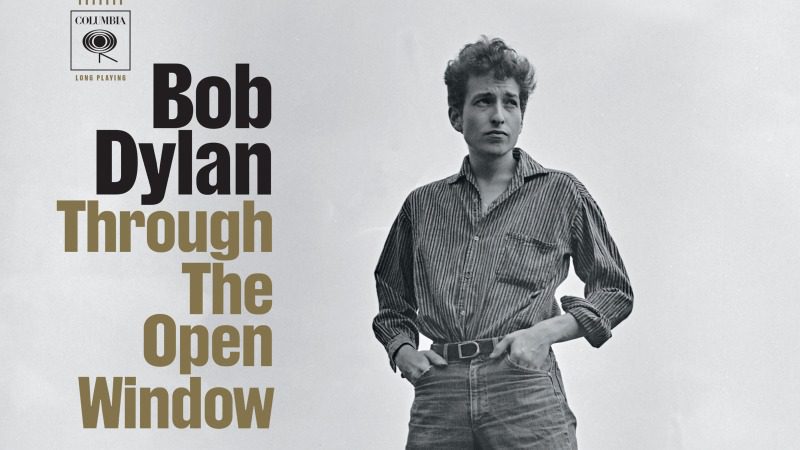

[Editor’s Note: The following review pertains to the 42-track “Highlights” version of this release; however, elements of the 139-track “Deluxe” set are also discussed for context.]

Bob Dylan has been confounding the expectations of critics and audiences alike for more than half a century. Over the last couple decades alone, he’s dispelled the notions that rock stars need to retire at some point, that tours must come to an end, and, in the case of his now-legendary Bootleg Series, that vaults eventually run out of treasures to dust off. The Bootleg Series volumes that have captivated fans most have managed to tell stories, not merely gather batches of artifacts. These stories have included transcendent live performances during transformative moments in Dylan’s growth as an artist; tour compendiums that find him shaking up history and flexing new creative muscles; and extensive studio recordings that help explain how the albums and songs that have marked our times came to be. On Through the Open Window, the 18th installment in this series, which spans 1956-1963, listeners hitch a ride alongside a desperately young Dylan as his aspirations take him from smalltown Minnesota to the epicenter of the American folk revival in Greenwich Village and even the heart of the civil rights movement. It’s a beautifully documented journey that manages to poke holes in the idea of Bob Dylan as an almost-mythical figure while also increasing our appreciation for his singularity as an artist.

The first scratchy sounds heard on Through the Open Window take us all the way back to the Terlinde Music Shop in St. Paul on Christmas Eve 1956. A 15-year-old Robert Zimmerman and two friends belt out a rudimentary, woefully off-key rendition of “Let the Good Times Roll.” This could’ve been any trio of teenagers with a fledgling sense of rhythm goofing around on piano, but it just so happens to be the humble beginnings of Bob Dylan’s iconic career as a recording artist. And that’s a large part of what makes this volume so fascinating even though it’s not always the most accomplished collection of performances. It quickly shatters any illusion of Dylan having magically arrived in Greenwich Village as a fully-formed folk prodigy. Instead, we get to hear the growing pains on a home recording of “Jesus Christ,” a tentative Dylan more concerned with assembling the pieces of this Woody Guthrie song than putting any personal stamp on it. Likewise, an early recording of the traditional “Remember Me” smacks more of imitation than interpretation as Dylan focuses on nailing its cadences rather than pouring his own life experiences into this vessel. He’s still just kicking the tires on this whole folksinger thing, and yet, an early live recording like “Railroading on the Great Divide”—the first time here that we hear that unmistakable harmonica and an audience’s reaction—already captures the undeniable conviction in his voice and more than hints at the immense talent ready to be tapped into in the months to come.

It’s through the songs of others that we witness Dylan gradually begin to unlock whatever it is that makes him Bob Dylan. The simple words and melody of the tearful “He Was a Friend of Mine” require Dylan’s soft, plaintive vocal to carry the emotional heft and fill in the details of a lost companion. It’s a performance that still dampens eyes all these years later. The parting bluster of “Dink’s Song” now sounds like Dylan’s own account rather than borrowed sentiment as he belts out “fare thee well” through clenched teeth over a bouncing bunkhouse strum. Likewise, listeners would never suspect that the absent woman in “Corrina, Corrina” has troubled many a man before Dylan ever sang about her. As we hear him learning how to transform these songs into his own, early originals like “I Was Young When I Left Home” and “Tomorrow Is a Long Time” demonstrate how he then begins using the lonesome, wandering tropes of the folk tradition to find his own stories. From that point, it’s not difficult to listen to Dylan singing an early rendition of “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright” at the Gaslight and understand how he could have gotten there. And seeing that hard-earned progression surely doesn’t make the results any less breathtaking.

If the first half of Through the Open Window shows us Dylan becoming Dylan, then the remainder of the journey finds us—and probably Dylan as well—trying to keep up as versions of his earliest great works start bursting forth. An alternate take of scathing polemic “Masters of War” makes it clear that Dylan has learned not only how to make the political personal but also more topical than much of his antiquated folk repertoire. A live recording finds him urgently rushing “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll” straight to audiences. He masterfully delivers the tear-soaked lament—based on a racially charged murder ripped from newspaper headlines—several months prior to it landing on The Times They Are a-Changin’. Similarly, all the major elements of that future record’s title track are in place as Dylan asks an audience to “come gather ‘round” as he sings one of his few attempts ever to create, in his words, “an anthem of change.” Again, he’s writing, recording, and playing these songs for audiences in as close to real time as he can, almost as if he’s afraid the magic will wear thin by the time an actual album comes out. An alternate take of epistolary parting tale “Boots of Spanish Leather” stands out among the very best that Through the Open Window has to offer. Inspired by the distance caused by then-girlfriend Suze Rotolo’s travels abroad, the song shows Dylan drawing from the confusion in his own heart in a way that feels so much more poignant than borrowing from the tales of love and pining found in the traditional folk songbook.

Through the Open Window culminates in eight selections from Dylan’s landmark concert at New York’s Carnegie Hall in October of 1963. In just a little over two years on the folk scene, he’d gone from playing clubs and any room that would have him to giving a command performance in front of a sold-out crowd of more than 3,000 people. Applause rings out through the cavernous hall for a powerful, hypnotic rendition of “A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall” and as Dylan strums and blows his harp in the preamble to “Blowin’ in the Wind,” already a hit for folk trio Peter, Paul and Mary and a burgeoning civil rights anthem. However, we equally sense the degree of Dylan’s rise when the room hangs on every word as he charmingly stumbles through an anecdote or jokingly asks “Mr. Carnegie” for technical help with a misbehaving microphone. Perhaps even more telling is just how receptive the crowd remains during songs they don’t know yet and won’t hear again until The Times They Are a-Changin’ drops the following February. Most poignantly, Dylan fills the hall with images of nature’s own melody on the debut of the beautiful ballad “Lay Down Your Weary Tune,” a song he had recorded only a few days prior. The depth of this recording speaks to both Dylan’s rapidly emerging command as a performer and the urgency he must have felt as songs were coming faster than he could possibly share them.

The “Highlights” edition of this release necessarily abridges the story this volume sets out to tell. If the sprawling “Deluxe” version acts like a long, winding trainride, then we can think of this edition as an express; the destination remains the same, but there are less stops along the way. Naturally, this steepens the slope of Dylan’s growth as an artist, offering fewer glimpses as he stumbles, regains his balance, and bounds forward both as a songwriter and performer. A more notable sacrifice are some of the choice moments that remind us of just how unpredictable Dylan’s journey turned out to be and how, as liner notes author Sean Wilentz notes, community contributed to Bob Dylan becoming Bob Dylan. Here, we miss most of the stories, interviews, and song introductions from Dylan that help color the Greenwich folk scene and the politics of the time. It’s understandable, if a bit saddening, that compilers had to leave out Dylan spinning yarns about his past life in the circus or recordings of him sitting in as a harmonica session player (highlighted by Harry Belafonte telling him to “take your time … take off your boots” during a rehearsal of “Midnight Special”). It’s far more disappointing that if there could only be one version of “Only a Pawn in Their Game,” it’s not Dylan famously singing in front of a flatbed truck at a SNCC rally in Greenwood, Mississippi. Indeed, this is a volume of the Bootleg Series that truly warrants the “Deluxe” upgrade to enjoy every enriching signpost along the roadside.

An old joke asks, “How do you get to Carnegie Hall?” The punchline, of course, is an emphatic “Practice!” In many ways, Through the Open Window serves as Dylan’s own roaming, rambling account of how he quite literally made it to that historic venue after only a few short years on the folk scene. As this volume shows, it’s a route that took him from the Midwest of his youth to the heights of New York City bohemia, up to the Great White North and down through the Deep South, from living room concerts and hole-in-the-wall cafes like the Gaslight to the steps of the Lincoln Memorial where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. told us all about his dream. And yet, as much as Through the Open Window is about Dylan’s arrival, it’s also a farewell of sorts. At this point, he’s already got visions of electric guitars and Rimbaud and the Beats bouncing around his brain, and, as would become typical of Bob Dylan throughout his career, he’ll soon close this particular window and crawl through another. But that’s a story for another bootleg.