It’s difficult to conceive from today’s perspective, but hearing Black Sabbath for the first time in the early 1970s had to have been an earth-shattering experience, particularly for listeners still in the adolescent throes of music discovery. We know this because dozens of them who went on to form famous bands have expressed a reverence so devout, it’s as if Black Sabbath’s music defines who they are at the core of their being. Although fellow figureheads like Led Zeppelin, Deep Purple, Alice Cooper and even Funkadelic helped sow the seeds of what would eventually come to be known as heavy metal, Sabbath were indisputably the first to bring those seeds to fruition.

At the time, there was simply no precedent for the dense, ominous twist that Sabbath put on the rock template, and it’s no exaggeration to describe the Birmingham, England quartet’s self-titled debut in terms of a Big Bang-scale event that birthed a new musical universe. By the same token, the band’s work can have just as profound an impact on one’s musical perspective in the present day, even with multiple generations of musicians having built on the initial foundation. Much like Beatles-inspired harmonies can be found everywhere in pop music, the influence of guitarist Tony Iommi’s riffing style is so pervasive that it’s become a kind of public-domain library to draw from. Without Iommi, entire movements like stoner rock, sludge and doom metal never have a basis to form.

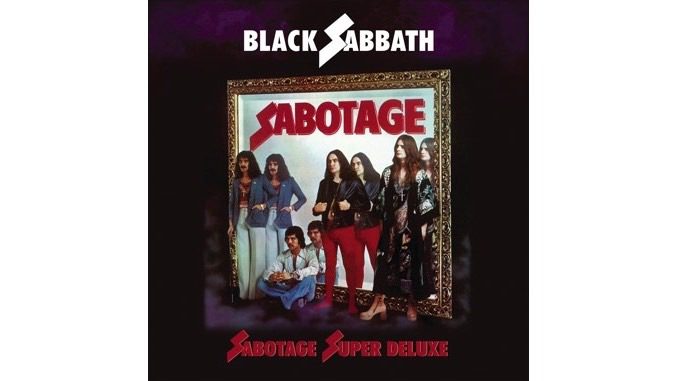

Oddly, though, scores of bands who owe their existence to Black Sabbath have focused only on the band’s most superficial qualities. With countless Sabbath covers attempted by everyone from Charles Bradley to Cannibal Corpse, it’s telling that so many marquee hard-rock acts—Soundgarden, Kyuss, Faith No More, Metallica, Pantera, White Zombie, Al Jourgensen, Weezer, etc., etc.—haven’t come close to capturing the nuance or dynamics of the originals. Which indicates that there’s something about Black Sabbath that’s impossible to pin down, much less replicate. And anyone who sees the band according to a confining definition of metal is in for a world of surprise with Sabotage, an album that’s every bit as flamboyant and strange as the band looks on the cover, dressed in a motley assortment of loud ‘70s clothing—except that the music has aged far better than the outfits.

For simplicity’s sake, Black Sabbath’s classic-era work with original vocalist Ozzy Osbourne divides into two distinct periods: a four-album block consisting mainly of the metallic, funereal style the band is celebrated for, and another four-album block of more exploratory material that showcases Sabbath stretching out in myriad directions. That said, the first four albums can hardly be considered one-dimensional affairs. At points, Black Sabbath (1970), Paranoid (1970), Master of Reality (1971) and Vol. 4 (1972) all deviate sharply from the forbidding ambience that so impressed the band’s musical heirs. And even when those albums stick to a uniform approach, they contain an enormous amount of texture—not to mention residual traces of the band’s roots in blues, psychedelia and jazz along with splashes of hippie flower-power sentiment that add yet more contours to the music.

Conversely, it’s in the second phase of the Ozzy era where we find some of the most crushingly heavy Sabbath tracks. Sabotage, the band’s sixth effort, epitomizes Sabbath’s hunger for variety during this period. And, while Iommi, bassist/chief lyricist Geezer Butler and drummer/secret weapon Bill Ward saved their most audacious creative gambles for the fusion-jazz forays they would take two albums later on 1978’s Never Say Die!, Sabotage stands apart from the rest of the catalog for the deranged glee that permeates every note. Even the way the album starts—with six seconds’ worth of near-silence as someone (presumably Ozzy) playfully shrieks in the distance—has a warped touch.

“Hole in the Sky,” “Symptom of the Universe,” and passages from the centerpiece epics “Megalomania” and “The Writ” feature Iommi’s signature riffing style, which is captured by engineer/co-producer Mike Butcher as a thick, molten—even slightly acidic—froth of sound that comes to a low boil before pouring out your speakers. But after introducing strings, flute, a slew of synths and Yes keyboardist Rick Wakeman to their sound on 1973’s Sabbath Bloody Sabbath, it only makes sense that the band takes things further out with Sabotage. This time around, though, Iommi and his bandmates focused a bit less on exotic instrumentation and more on creating a sense of novelty through maze-like song structures and sudden shifts in mood that induce a slight (though not unpleasant) feeling of disorientation.

Among its many twists and turns, Sabotage practically dares listeners to keep up with each successive off-kilter element: oddly dissonant classical guitars, backwards cymbals slurring against the mix as if sucking the listener into the surreal headspace of a dream, an airtight feeling of enclosure as the sound contracts around bass flickering through a wah-wah pedal, and so on. And no matter how many times one listens to the instrumental “Supertzar,” the flavor never gets any less unfamiliar. It’s as if, one day in the studio, one of the band members was tripping on LSD and said, “Hey, what if we imagined the score to a Disney adaptation of the life of Josef Stalin? Now that would be heavy … ”

Throughout, a sense of creative restlessness abounds as songs morph radically from one section to the next. The first two thirds of “Symptom of the Universe,” for example, lay down a proto-speed metal blueprint with an uptempo chug that’s as driving and sinister as one would ever want their metal to be. But then, with a whoosh, the listener gets dropped into a wide-open musical realm somewhere between Santana, America and Django Reinhardt with soft acoustic guitars, tasteful hand percussion courtesy of Ward, and Osbourne cooing: “In your eyes, I see no sadness / You are all that loving means / Take my hands and we’ll go riding / through the sunshine from above / We’ll find happiness together / in the summer skies of love.”

On paper, the mishmash of styles reads like a hairpin turn that would send even the most versatile groups toppling—especially when the members of Sabbath paint a picture of themselves in a clown-car phase of their career around this time. By their own admission across various sources (including the new liner notes), Sabotage is their third album where drug abuse was rampant to alarming levels. Osbourne, meanwhile, was by this point increasingly at odds with Iommi’s conviction that Sabbath could tackle any musical style they wanted to. To make matters worse, this time they found themselves embroiled in an all-consuming legal battle with former manager Patrick Sheehan.

With the band broke, embittered, emotionally drained by the lawsuit, grasping to learn how to manage its own business affairs and addled by mountains of drugs, along with the cracks of creative friction starting to take their toll, Sabotage had all the makings of a colossal mess. Sure enough, though, the “Symptom” transition goes off so smoothly that the change isn’t even slightly jarring for the listener. In fact, the oddest thing about Sabotage is that the music never once unravels. For all the curveballs the band throws, it doesn’t actually lose its sense of direction, purpose or surefootedness. “Thrill of It All,” for example, shows that Black Sabbath could be eerie, reproachful and uplifting, all in the same tune. Crucially, they were also exceptionally capable of developing a dramatic arc, with gripping emotional peaks and valleys, all within a relatively concise timeframe.

Without question, the band’s knack for arrangements was still in peak form at this point—although “The Writ” and “Megalomania” stretch well beyond the 8-minute mark, every single change on the album serves its function to propel the music forward. As a result, medium-length tracks like “Thrill of It All” and “Symptom of the Universe” feel much longer than they actually are, and the album as a whole coalesces into a coherent 43-minute flow, where every track ends on a satisfying note of resolution—a shock when you consider how many ideas were thrown at the wall here, but not so shocking in light of how much the band’s collective songcraft had matured by Sabbath Bloody Sabbath. If Sabotage is indulgent style-wise, the band maintains the necessary focus to make that indulgence look like genius.

Aside from a sterling, unobtrusive remastering job—kudos to mastering engineers Andy Pearce and Matt Wortham for opting not to artificially magnify anything about the mix—the real selling point with this new edition is the inclusion of a complete live show recorded a week after the album’s release, on Aug. 5, 1975, at the Convention Hall in Asbury Park, New Jersey. Diehards will no doubt be familiar with the existing bootleg of the same performance, as well as the prior release of three tracks from that night on the double live album Past Lives. Hot on the heels of the full 1973 concert included with Rhino’s deluxe reissue of Vol. 4 just a few months ago, it would be understandable if fans felt wary of jumping at the bait one too many times, considering that much of the bonus Vol. 4 live disc had already been packaged twice (with better sound quality, no less) as Past Lives and Live at Last.

If you’ve listened at length to any of those releases (or seen video footage of the band’s Paris show from 1970, its 1974 appearance at California Jam, its 1978 set from London’s Hammersmith Odeon, etc.), you’re not necessarily going to find anything revelatory here. Aside from a handful of songs newly swapped into the setlist, the pacing, spirit and overall attack of the Asbury Park show mirror the 1973 gig in most respects. However, the newly brushed-up live recording—which significantly improves on the sound of the bootleg—takes the cake for the most accurate and well-rounded live document of Black Sabbath in the ‘70s. Now, listeners won’t be forced to choose between full sound/truncated setlist on the one hand and full setlist/stiff board mix on the other. Finally, fans can come as close as possible to transporting themselves back and experiencing a whole show as if they were standing in the arena.

Some caveats: Purists may scoff at the presence of longtime Robert Plant keyboardist Gerald “Jezz” Woodroffe, and you should remember going in that this was, after all, the mid-’70s. Which means that the setlist kicks like a mule for the first several selections before the band goes off-roading in improv mode. We can deduce from this recording, though, that Sabbath were keen to avoid the interminable jams that take up entire sides on Zeppelin’s Song Remains the Same and Purple’s Made in Japan. At one point towards the end of Ward’s drum solo, someone—whether it’s a member of the crew, the band or Ward himself is unclear—jokingly yells “drum solos are booo-riiiing!” loud enough for the mics to pick it up. It’s also priceless when Ozzy, also with tongue in cheek, asks the crowd: “Are you hiiiiiiiiiigh? So am I!” and quips that he doesn’t remember how “Paranoid” goes.

Advertised as a “four-disc set,” Sabotage Super Deluxe is more truthfully described as a three-disc set that includes an additional two-song single (both radio edits, packaged in a Japanese-language sleeve design). And unlike the super deluxe edition of Vol. 4, there are no studio outtakes this time. What you get is the remastered album plus the concert, which takes up two discs. The absence of works in progress, however, only helps to draw one’s focus back to the album itself. In truth, Sabotage benefits by remaining shrouded in mystery. And the hardbound liners, though certainly handsome, don’t enhance the experience by harping on the legal woes that hung over the proceedings.

Even once you learn that “The Writ” got its title (and its undercurrent of anger) from the band being served court papers in the studio, there’s really no need to take music that carries you away to the outer reaches of your imagination so effectively and anchor it in the earthbound tedium of a lawsuit between a band and its former manager. Sure, there’s some charm in trying to picture Ward as the person designated to field calls during the recording process (as Osbourne described in his 2009 memoir I Am Ozzy), but Sabotage occupies the senses on levels that extend well beyond the conditions it was made under. Like all of the band’s first eight albums, it operates on a magical four-way chemistry that defies words—a chemistry that mostly refuses to translate when other musicians, no matter how gifted, try to get their hands around the same material.

As a portrait of a multi-faceted band pushing itself to be ever more daring, Sabotage still glimmers with intrigue and the allure of limitless creative possibility, even four and a half decades on.

Saby Reyes-Kulkarni is a longtime contributor at Paste. He believes that a music journalist’s job is to guide readers to their own impressions of the music. He also dreams of being a “setlist doctor” to the bands you read about in these pages, and has started making playlists for imaginary shows that your favorite band never actually played. You can read his work, listen to his interviews and playlists at feedbackdef.com, and find him on Twitter.