If there’s anything we’ve learned about Robert Smith in his 44 years as The Cure’s frontman, it’s that he will never be what you say he is. He refuses all labels anyone attempts to push onto him or his work. “Goth” tends to be the word to which he has the most aversion, attributing his distaste for the term to constant lazy puff pieces about the group by writers who have run out of words to use when describing something intense or dark.

To an extent, the term makes sense when it comes to defining The Cure and their atmospheric, misanthropic skew on the world that they manage to express purely through instrumentation on albums like Pornography or Disintegration (the former of which literally opens with Smith singing, “Doesn’t matter if we all die!” without even the slightest hint of doubt or hesitation). In another way, he’s completely correct about the “G” word and its misuse; few goth bands would ever let pop oddities “The Lovecats” and “Let’s Go to Bed” see the light outside of the studio, or proudly continue to play the Buzzcocks-inspired pop-punk songs of their early career like the evergreen “Boys Don’t Cry,” both of which The Cure did.

A darkness has remained throughout all of it, no question about that. But, if anything, The Cure have always been more about emotion than just edginess or darkness for darkness’ sake; substance of the heaviest kind over style. If the nerves went dead, there’d be nothing left for Smith to sing about. If the heart stopped bleeding, he’d simply stop working. Even “nihilistic” Cure feels the need to thrash around for an escape. It’s a band that most hardcore fans (a group in which I would include myself) take personally on an intense level, not for shared lack of feeling, but shared sensitivity or a sense of connection. For the knowledge that even as we scale cold, lifeless walls, there will be a warm hand to grip onto with our own. “Oh no, love, you’re not alone! / Give me your hands,” David Bowie, a major influence for The Cure from their inception onwards, had written 15 years prior to the release of The Cure In Orange. “And it’s so cold, it’s like the cold if you were dead / Then you smiled for a second,” Robert Smith would write himself, two years after its release.

Despite the wealth of concert material Cure fans have access to at this stage in their storied career, one film stands above the rest as a thesis statement for the band and why they remain deathless after so many years. All of their magic, of both the light and dark varieties, is on full display in Tim Pope’s The Cure In Orange, which celebrates its 35th anniversary today (Feb. 23). Filmed in August 1986 at The Cure’s run of shows at the Roman Theater of Orange in France to promote 1985’s The Head On the Door, and released only a few months before 1987’s double album Kiss Me, Kiss Me, Kiss Me, In Orange serves as both a bookmark in and a crown jewel of the band’s career.

One essential lightning crack in this perfect storm is the presence of what is considered by many to be the band’s best lineup. With Smith handling guitar and lead vocals, accompanied by guitarist Porl Thomson, Boris Williams on drums, and original members Lol Tolhurst and Simon Gallup on keyboards and bass, respectively, the band is an absolute force onstage, even if we’re limited to experiencing their power through a screen. Another move in the concert’s favor is the venue where it was filmed: The Roman Theater of Orange (known as Théâtre antique d’Orange in its home country) was built into a hillside of the Rhône Valley during the days of the Roman Empire. Massive in scale, imposing, and carved with stunning detail that you’d probably miss if you only visited once or twice, the theater appears to visually swallow these small figures in dark makeup whole, but it meets its match in the sound those figures make. This is the type of venue their music demands.

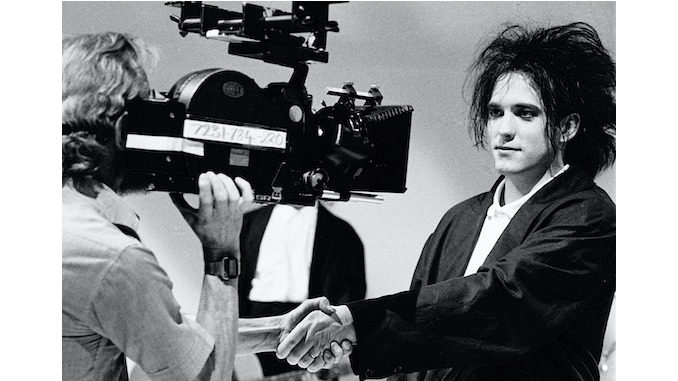

Another piece of the puzzle comes in the form of director Tim Pope, who began collaborating with the band beginning with the video for 1982’s “Let’s Go to Bed,” and has worked with them through to the present, most recently directing the band’s Anniversary: 1978-2018 – Live in Hyde Park London concert film. All the way through his extensive working relationship and friendship with Smith, he’s proven to be the ideal visual conduit to capture all of the band’s silliness, claustrophobic paranoia and often painfully heartfelt sincerity in the form of the three-minute, commercially viable music video. His work in the context of a feature-length concert film has the same effect, playing with the scale of both the venue and the drama of the songs while also zeroing in on each member of the band, washing their expressive, painted faces in rainbow colors, bringing the light out of each person in the process.

The final essential ingredient comes in the setlist, which requires some context in the form of an ultra-brief history of the band up to the time of In Orange. Smith and Tolhurst (soon to be joined by Gallup) formed The Cure with their friend Michael Dempsey in Crawley, West Sussex, released their debut album in 1979 amidst the death of punk and emergence of British post-punk, and went on to release progressively darker, more complex albums for the next four years (pay attention, this is where the “goth” tag comes into play). The trilogy of Seventeen Seconds, Faith and Pornography gained the group traction with the alternative music press and allowed them to amass a cult following. After the release of 1982’s Pornography, which remains part auditory assault and part emotional meltdown put to record, Smith reached a personal breaking point and dissolved the band … until he decided it wasn’t dissolved any longer.

Before rebuilding The Cure, Smith wrote the most nonsensical, poppy songs he could as a middle finger to the gloomy image that had grown up around his group and, always the contrarian, recorded them with the silent hope that it would alienate their entire fanbase. The songs in question were “Let’s Go to Bed,” “The Walk” and “The Lovecats,” all of which were featured on a compilation of The Cure’s material from the period titled Japanese Whispers. Even as The Cure became MTV fixtures (a shift that probably perplexed Smith even more than the “morose” label), they found themselves in a weird place within the musical landscape of 1983: too mainstream for a good chunk of the indie kids who built them up, yet so unwilling to play the game that MTV couldn’t mold them into video stars ready to kill. Case in point: Their most accessible song up to this time, “The Lovecats,” had a creepy, proto-Tim Burton video seemingly meant to make any newcomer think twice before humming along. They once again didn’t quite fit into any pre-made mold—exactly the way Smith liked it.

In 1984, The Cure combined their new fondness for all things off-kilter and candy-colored with the sounds of their past to create the bizarre (and still criminally underrated) The Top, before kicking 1985’s door down with The Head On The Door, arguably the perfect blend of their dark intensity with listener-friendly hooks. It provided their first taste of international success, stands for many as their best record pre-Disintegration (and for some, their best, full stop), and made for perhaps the purest representation of the band we had seen thus far. In other words, when people think of a stereotypical Cure song, they’re thinking of something that sounds like “In Between Days,” “Close to Me” or “Push,” all three of which get their moment to shine on a stage of literally empiric proportions during In Orange’s runtime, right where they belong.

Despite the various incarnations we’d seen of the band to this point, the film’s tracklist flows seamlessly from era to era. Icy, hollow Faith-era single “Charlotte Sometimes” is followed by new track “In Between Days,” the transition going off without a hitch. Chaotic The Top deep cut “Give Me It” sounds at home next to “10:15 Saturday Night,” the straightforward opener from the group’s debut. Though the level of intensity varies, sheer emotional release ties every point in the setlist together. There’s no mistaking that each song comes from the same pen, the same rich internal world, even when the lyrics are supposedly nonsensical. For the show’s version of “Let’s Go to Bed,” Smith’s bastard child of a song that he claimed was a parody of radio-friendly pop, he eschews his guitar to dance around in what seems like an attempt to convey how unseriously we should be taking it. Yet there’s a point where the mostly warm-toned stage lights (the movie has its name for a reason) turn blue during the song’s first refrain. As Smith sings, “And I don’t care if you don’t / And I won’t feel if you don’t,” he stares at his feet almost shyly for the first time in the entire set, and right then, you don’t believe that line for a second. After all, we just heard him beg, “Please love me!” during “One Hundred Years” a few songs ago. Even in the show’s lighter moments, it’s still heavy with feeling. It’s like the band can’t help but be sincere, can’t help but tell when they’re lying, hiding in plain sight.

That shockwave of unfiltered emotion is something Cure fans don’t take for granted—it’s more like their image reflected back at them. Personally, I’ve always been sensitive to a fault, annoyingly wounded by the way the world around me inevitably pushes back. What might appear to others as shyness was simply an inability to risk setting something off that would leave me reeling emotionally for days afterwards. Contrary to what logic might dictate, people who experience the world this way tend to grow thicker skin in order to avoid the sting, building up stone walls that only let the gates open when they are sure conditions are safe. Due to those long periods where all thoughts and feelings are under lock and key, they come forward in painful bursts when those gates are unlocked, almost certain to drown whoever is not willing to be a sponge. There are days where I’m fine, and other days where normal interactions are like pulling teeth for me. I’m still not convinced that it isn’t a weakness, but Smith, and specifically the set of his songs presented in The Cure In Orange, have been a crucial part of my realization that it’s something to honor, to hold sacred. To be a radical, unabashed fount of emotion in a world that does not make space for such a thing is a source of power. Smith’s feelings rush forward, taking a battering ram to our own walls with the gradual crumbling of his, and it is a gift. Perspectives shift, preconceived notions of identity vanish, and we are allowed to feel with him. The ability to laugh at yourself is essential, as well, and as we’d seen from those not-quite-pop one-off singles, he has that in spades. I’d like to think I do too, despite it all.

It comes down to that compulsive urge to record those extreme highs and lows as if to prove that they happened, that the searing catharsis was better than feeling nothing, and to have a crowd of thousands witness this indisputable truth. Between Smith’s pleas to “come back, come back, don’t walk away,” assertions that “It’s always the same / I’m running towards nothing / Again and again and again,” and confessions that “I’m coming to find you if it takes me all night / A witch hunt for another girl / For always and ever is always for you,” everyone present then or still watching now is bound together in communion. It’s that old boring term—life-affirming—and even joyous. To quote the simplest description of The Cure ever uttered on film, they’re what the music-savvy brother in John Carney’s Sing Street refers to as “happy-sad.” I’m not sure if Smith himself gave the go-ahead to use the band’s music in that movie, or if that’s someone else’s job and he’s not familiar with it, but I think he would prefer that descriptor over “goth” any day.

For someone who has long claimed to be uncomfortable speaking to journalists and audiences alike (though he’s endearingly opened up just a bit as time goes on), Smith has never been afraid of laying his inner life bare on a stage in song. I know next to nothing about what he’s like in real life, and yet I am still awestruck by how carries himself with so much certainty when he sings of sensation, what he knows to be true, especially since he claims much of the material is autobiographical (“Obviously, the ones where I drown aren’t from direct experience”). In that way, he’ll always feel familiar to those of us to hold The Cure close, like someone who swims in the same deep water as you, holding your hand tightly in his through your headphones. “And it’s so cold, it’s like the cold if you were dead / Then you smiled for a second.”

And sure, that’s intense. Our impulse is to make room for other people’s comfort, boxing up eccentricity or that which seems melodramatic to others standing at a different viewpoint. Even if you call it dark, Smith seems to know it’s not so much a darkness, but a fearlessness—maybe even a sense of wonder—which, in its own way, holds so much more weight.

Elise Soutar is a writer, musician, friend of witches, wannabe punk and annoying New Yorker. You can watch her share the same pictures of David Bowie over and over again on Twitter @moonagedemon.SXvEVl9MFB4

Listen to a 1984 Cure performance from the Paste archives below.