In 1987, Chuck Roberts was called into a recording studio in Chicago to deliver a short sermon on house music for Rhythm Controll’s “My House,” a record that became synonymous with a genre.

In the beginning, there was Jack, and Jack had a groove

And from this groove came the grooves of all grooves

And while one day viciously throwing down on his box, Jack boldly declared

“Let there be House!” and house music was born.

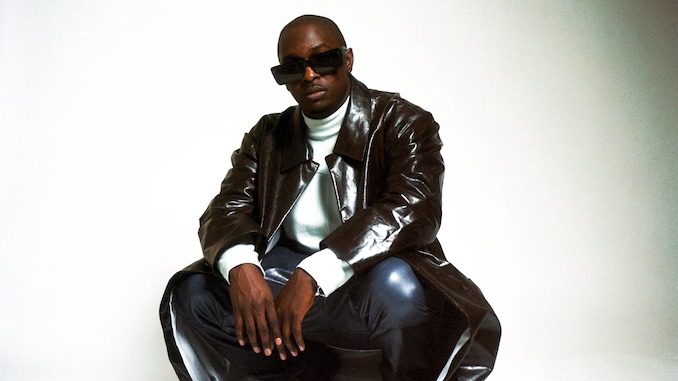

Born a year before “My House,” Nesbitt Wesonga Jr. delivered a sermon of his own with his 2020 solo debut “Wild Youngster,” featuring longtime collaborator ScHoolboy Q. While Wesonga, who goes by NEZ, may disagree with the comparison, the Windy City native’s purist approach to dance music and hip-hop is bridging the gap between the two worlds.

From how he describes it, his upbringing was simple. NEZ was born in 1986 in Chicago to an American mother and Kenyan father, initially exploring music throughout childhood as a church drummer until he was old enough to explore the streets of Hyde Park in his teenage years.

Embedded within the rich lineage of Chicago were the city’s unique brand of blues, soul and gospel, which gave way to the birth of house music and laid down the framework for a bustling hip-hop scene. By the mid-to-late 1990s, as the mainstream appeal of hip-hop grew steadily with acts such as Common, Crucial Conflict, Twista and Do or Die breaking onto the Billboard charts, Chicago house had reached its peak in popularity. NEZ happened to be in the middle of it.

“There were definitely two separate scenes going on,” NEZ explains. “It was more noticeable in the generation before me, because by the time I started coming up, things started getting blurry. But still, the people I’d see skateboarding and listening to hip-hop were not always the same people I saw on the house side of things.”

Nonetheless, the parallels have always been there. Both genres of music were born out of the reinvention of Black music combined with newer technologies, serving as both a home and an outlet for the marginalized. Whether it be the reflections of wealth on Common’s “Chapter 13,” in which he says, “See I make money, money doesn’t make me / I’m a reflection of my section and my section 8,” or the underground house clubs that primarily catered to gay Black and Latino men, hip-hop and house music served Chicago’s most vulnerable.

“Both genres that I’m bridging the gap on started because they felt that they were excluded. A lot of the people don’t realize the pioneers of house music are Black and Latino gay men. On the rap side, they felt like all they had was these turntables and a microphone to be able to create the music that they felt was in their hearts.”

For NEZ, Chicago’s music was inescapable, with car stereos, cracked-open windows on Sunday mornings, and his own household teeming with generations of musical history. One particular avenue for his musical discovery was his local rollerskating rink, a sacred space for many Black Americans dating back to the civil rights movement. What started as a designated night for Black families to go to the rinks during segregation turned into a safe haven for Black expression post-civil rights era, with rappers performing when venues wouldn’t book them to house DJs testing records on rinks before bringing them to clubs.

“If you were growing up in Chicago, starting at the age of 12 or even younger, you would go to Rink Fitness Factory or Route 66 or the other big Chicago rinks. Every Friday and Saturday, depending on which rink you went to, they would have these parties for kids 13 to 17 where they’d play house music super loud,” NEZ recalls. “But you’d hear everything, too, like reggae, ghetto house and R&B. I remember partying and just hearing so many styles of music in a four-hour period.”

NEZ began channeling the music he discovered into his own creations by tinkering with FruityLoops, a music production software that became popular for its accessible layout and was aimed toward casual creators rather than professional musicians. Iconic records such as “Threat” by Jay-Z and “Crank That” by Soulja Boy were made using the program, and it was records like that that inspired NEZ and his friends to imitate their favorite producers’ unique styles.

“My first beat was a ghetto house beat, but a few beats later, I was making rap beats because Kanye West was poppin’,” says NEZ. Indeed, West’s now-iconic production style was beginning to take form in the early 2000s, such as his work on “The Truth” by Beanie Sigel at the beginning of the decade, or 2001’s “Izzo (H.O.V.A) ” by Jay-Z. “Coming from Chicago, everybody wanted to follow those footsteps in some way, shape or form if you’re trying to do music, at least at that time. That was the entryway.”

By the time NEZ reached young adulthood and attended the historically Black Howard University in Washington, D.C., he had taken his church drumming background and the hours spent mimicking Dr. Dre and Quincy Jones’ styles to create his own unique sound. He teamed up with childhood friend Mario Loving to form a production duo called Nez & Rio. The two rose to success, initially producing for fellow Chicago native Vic Mensa and finding a frequent collaborator in ScHoolboy Q, with the latter connection garnering the duo a Grammy nomination for their work on 2015’s Oxymoron.

In the midst of managing being a highly sought-after rap producer, NEZ found himself in the studio on Valentine’s Day in 2017 working on his contributions to Schoolboy Q’s 2019 album Crash Talk when he decided to show the rapper what else he was working on. Instead of the lush, electronic-tinged trap-influenced beats he was known for, he played a house beat.

“I wanted to get his opinion because I respect him as an artist. So, I showed him ‘Wild Youngster’ and he lost it. He was like ‘Bruh, I’m hopping on this right now,’ and he wrote his verse on an iPhone in 15 minutes. We recorded it, and the song was done.”

Three years later, the collaboration materialized as NEZ’s head-turning solo debut, in part because of ScHoolboy Q’s expectation-defying feature on the thumping bass and rumbly synths. It was going to be a big year for NEZ, but then the pandemic hit. To him, it was a blessing in disguise. “I don’t think I was as prepared as I am now in terms of having an idea of seeing my artistry through. I was given a chance to get my shit together,” he explains. Thus, Midnight Music was born.

Released over a year after his debut, NEZ’s Midnight Music EP is a proper introduction to this other facet of his identity as a musician, allowing himself to take a more face-forward role in curating an homage to his city’s most sacred style of music. Spanning the three tracks are fragments of acid house, R&B, and techno, oozing with sensuality, luxury, and pride for the people and places that inspired NEZ. The EP even features house legend Felix da Housecat, widely known for his contributions to the second wave of Chicago’s house landscape.

Across most of his output so far, NEZ’s solo offerings still feature a growing cast of collaborators, ranging from Q and Felix to viral rap sensation Flo Milli and singer DUCKWRTH. It’s simply how he chooses to operate.

“Collaboration is key,” NEZ asserts. “Using people for what they’re good at, and letting people help you. From the outside looking in, you would think a lot of successful artists are just doing a whole lot of shit themselves. I think that’s the biggest thing that I’ve taken from this entire process. Community is everything. Everybody is important.”

It also speaks to the deeply communal nature of NEZ’s colorful environment, from being active in his church community to seeing DJs release collaborative mixtapes at the same roller rinks they performed at. The framework is set within his musical and cultural lineage, and he has adapted to carry them with him. He reflects on witnessing the change in technology and music, saying, “I’m old enough to remember MTV, but young enough to accept TikTok. I’m at a sweet spot. Being a young Black dude making dance music in a world saturated with EDM, I have a benefit of growing up in Chicago and being around when these important tracks were made. There’s so much of a world that we have forgotten.”

It’s a world NEZ has used his positioning to tap into and release to a wider audience, centered around an underlying joy that feels as radical as it is universal. Rapper 8AE stands in the middle of leather-clad dancers while NEZ’s 11-year-old niece flashes her grill that sparkles in the black-and-white filter of the “To The Money” video, embracing and reclaiming elements of Black culture within the context of his artistry. Nonetheless, he takes the approach that house music has had from the beginning: It’s for everyone. “We’re all humans,” NEZ explains. “We all have feelings, and we dance, we cry. We do all the same things.”

In the rest of Chuck Roberts’ seminal sermon on house music, he says:

I am the creator, and this is my house!?

And in my house there is only house music?

But, I am not so selfish because once you enter my house it then becomes our house and our house music!

And, you see, no one man owns house because house music is a universal language, spoken and understood by all.

NEZ understands that, and he’s spreading the gospel of house music one beat at a time.

Watch the fourth installment of NEZ’s Midnight Cut series below and listen to Midnight Music here.

Jade Gomez is Paste’s assistant music editor, dog mom, Southern rap aficionado and compound sentence enthusiast. She has no impulse control and will buy vinyl that she’s too afraid to play or stickers she will never stick.