My mother died in her own bed early in the morning of Sunday, April 11. This was entirely expected; she was 93, and her mind and body both had been failing for years. I wasn’t there when it happened, but I had been at her bedside the week before, trying to talk her down from the terrors when she woke up in the middle of the night. “Have I died already?” she cried out in her confusion. No, not yet, we told her.

And yet for all the warnings and preparations, it did make a difference when death finally arrived. One day she was there, and the next day she wasn’t. One day I had a mother, and the following day I didn’t. And it’s that absolute absence that’s the hardest thing to accept.

Whenever I’m in crisis, I turn to song for clarity and solace. It helps just to know that someone else at some time and in some place felt the way I do now. That doesn’t wash away the pain, but it does crack open the loneliness. It doesn’t change my feelings, but it lets me know those emotions are neither bizarre nor fatal. Seeing the situation through someone else’s eyes reveals aspects that I could never perceive through my own pain-clouded vision.

Songs have helped me get through romantic heartbreak, physical breakdowns and political nightmares. But when I went looking for songs that might help me through my mother’s death, I found them shockingly hard to find.

Oh, there are thousands of songs about death, even about the death of a parent. The internet yields countless lists of such songs. But almost all these songs have nothing to do with my experience of death: the irreducible absence it creates. In fact, most of these songs want to persuade me that that absence isn’t even real, that the recently departed are now in a better place, that we will meet again by and by, that the circle will be unbroken.

Those are nice thoughts, the product of good intentions, but they’re untrue. The dead are not in a better place; we will never meet again, and the circle is irreparably broken. The sentiments in these songs not only contradict every aspect of my encounter with death, but by denying my profound feeling of absence, they also insult me.

Don’t get me wrong. When I’m not in crisis, I can enjoy a song such as the Carter Family’s “Will the Circle Be Unbroken,” the Black gospel hymn “We’ll Understand It Better By and By” and the old Irish-American vaudeville tune “Danny Boy.” All three boast gorgeous melodies and all extend a generous feeling of comfort to the sorrowful. But they all negate my actual experience of death and are thus worse than useless in a situation like this.

Most modern songs about death are merely variations on this same theme. Vince Gill’s “Go Rest High on That Mountain,” Eric Clapton’s “Tears in Heaven,” Luther Vandross’ “Dance with My Father,” Mariah Carey’s “One Sweet Day,” The Band Perry’s “If I Die Young,” and the other songs that show up on those internet lists all respond to the anguish of absence by pretending it’s not real. That’s not much help if the reality of absence is what you’re trying to get a handle on.

So where are the songs that unflinchingly confront the terrible vacancy that death leaves behind? Where are the songs that acknowledge the terrifying finality of death? Because if that’s what you’re feeling, those are the songs you need.

Those songs exist, but you won’t find them under the spotlights of popular culture. You have to hunt for them in the shadowy corners. The older the corner, the better luck you’ll have. Ancient blues and folk songs never had to worry about finding a place on a radio station selling commercials, so they didn’t have to pull their punches when talking about death.

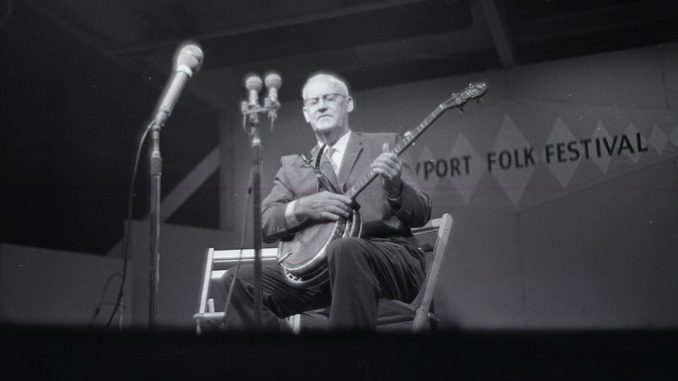

To hear the deep dread that comes with dying in the real world, there’s no one better than Dock Boggs, the Virginia coal miner who captured the true terror of death in his recordings from the 1920s. “Sugar Baby” is the moaning of a husband who has just buried his wife. Over the prickliest of banjo parts, Boggs’ stony baritone acknowledges the state of things: “Laid her in the shade, gave her every dime I made, what more could a poor boy do? … Got no sugar baby now.” There’s no false hope of a later reunion, just the bitter truth that the red rocking chair is empty and will never rock again.

Boggs also recorded one of the oldest known versions of “O Death,” a dialogue between a dying man and the Grim Reaper. “ With ice cold hands,” the latter takes hold of his victim, promising, “I’ll fix your feet so you can’t walk; I’ll lock your jaw so you can’t talk. I’ll … drop the flesh up off the frame—dirt and worm both have a claim.” Ralph Stanley based his famous version from O Brother, Where Art Thou? on Boggs’ model. But the earlier recording has no Ku Klux Klan choreography to distract one from the chilling facts of the matter.

Perhaps no song better captures the finality of death than the old blues song “Delia” (also known as “Dehlia”). When the narrator describes the young girl’s body in the hearse, he sings, “They took poor Delia to the graveyard, boys, but they never brought her back.” It’s a one-way trip, and no amount of fantasy can change that.

This song, based on the real-life murder of 14-year-old Delia Green in Savannah, Georgia, in 1900, has been recorded by many artists—Bob Dylan, Johnny Cash, Blind Willie McTell, Harry Belafonte, Waylon Jennings and more—but the finest, most dread-filled version is David Bromberg’s recording of it on his 1972 debut album. What’s the difference between the unhappy and the dead? “Curtis in the jailhouse,” Bromberg sings with a Boggs-like implacability, “drinking from an old tin cup. Delia’s in the graveyard, boys, and she may not ever get up.”

It’s fair to ask why anyone would prefer as song as bleak and unyielding as this one over a song that offers comfort and reassurance. Unlike songs such as “Go Rest High on That Mountain” or “Danny Boy,” which are designed to help you have a good cry and feel better afterward, a song like “O Death” or “Delia” leaves you so shocked that crying seems irrelevant. So why do I find myself turning toward the latter?

Because they’re true. They validate the actual experience of death. They confirm that our instinctive response to the event is valid. We’re not crazy; other folks also recognize death for the ugly, final thing it is. And in that shared recognition of reality, there is a communion more comforting than any false promise.

My mother was a religious woman; she believed she was going to heaven. But her body knew better; her nerves and muscles knew they were facing extinction, and they fought hard against impossible odds. It’s always that way. Whatever the threat—bullet, tumor, toxin or clot, whatever the belief system in the mind—paradise or reincarnation, the body will struggle for its very existence. When that struggle becomes a losing battle, it’s not a pretty sight.

So I don’t want songs that prettify death, repainting it as a door to an afterlife. I want songs as devastating as Neil Young’s “Tonight’s the Night.” This song about Young’s former roadie Bruce Berry, who died of a heroin overdose in 1973, captures the shock of death as few songs ever have. “People let me tell you, it sent a chill up and down my spine,” Young sang over brittle, splintering guitar chords more frightening than the words, “when I picked up the telephone and heard that he’d died out on the mainline. Tonight’s the night.”

I want a song as open-eyed as Bob Dylan’s “Not Dark Yet.” “Knocking on Heaven’s Door” is the more popular Dylan song about death—it certainly has a better melody—but “Not Dark Yet” is more honest. It captures those final weeks when a person realizes that death is coming soon, even if it hasn’t arrived yet. “I was born here, and I’ll die here against my will,” he sings, “every nerve in my body is so naked and numb.” He’s no longer bargaining with the universe for a different fate, a little more time. He has accepted the inevitable. “Don’t even hear the murmur of a prayer,” he adds. “It’s not dark yet but it’s gettin’ there.”

I want a song as unsparing as Louis Armstrong’s “St. James Infirmary Blues.” The narrator goes looking for his missing woman and finds her in the hospital “stretched out on a long, white table, so cold, so sweet, so fair.” He concludes that he’ll never see her again in this world or any other; all he can do is “let her go, let her go.” He spends the rest of the song imagining his own funeral.

I want a song as uncompromising as Vern Gosdin’s “Chiseled in Stone.” This country ballad begins as a conventional weeper about a romantic breakup. But the narrator is suddenly awakened from his self-pity when he’s confronted by an old man who has lost his wife to death. “You don’t know about sadness till you’ve faced life alone,” the old-timer tells us. “You don’t know about lonely till it’s chiseled in stone.”

I want a song as ironic as Dave Alvin’s “The Man in the Bed.” In describing his dying father, Alvin draws a contrast between the shrunken man in the hospital bed and the man’s self-image in his still-active mind. The man can imagine himself chasing the nurses around the ward and swinging a sledgehammer on the railroad. Taking on his father’s voice, Alvin sings, “These tremblin’ hands, they’re not mine; now my hands are strong and steady all the time.” But those trembling hands are his; the doctors aren’t lying, and he really is dying. Seldom has the contradiction at the end of life between who we think we are and who we really are been so well captured.

I want a song as cruel and unforgiving as Randy Newman’s “Old Man.” As in Alvin’s song, the narrator is in a hospital room with his dying father, but this narrator will not indulge his old man’s fantasies. “Won’t be no God to comfort you,” Newman sings, “you taught me not to believe that lie.” But the immense sadness of the piano chords undercuts the son’s arrogance, for he realizes that eventually he will face the same fate. “Don’t cry, old man, don’t cry,” sings the son. “Everybody dies.”

Yeah, everybody dies: my mother, Newman’s father, Alvin’s father. And all of us will die: me, my siblings, my son, everyone reading this. And we need songs strong enough to help us cope with that non-negotiable fact. There are a few such songs, but not nearly enough. I’m sure there are some that I’m not aware of (and I’d love to hear about them). But every songwriter alive now should aspire to write a new one.