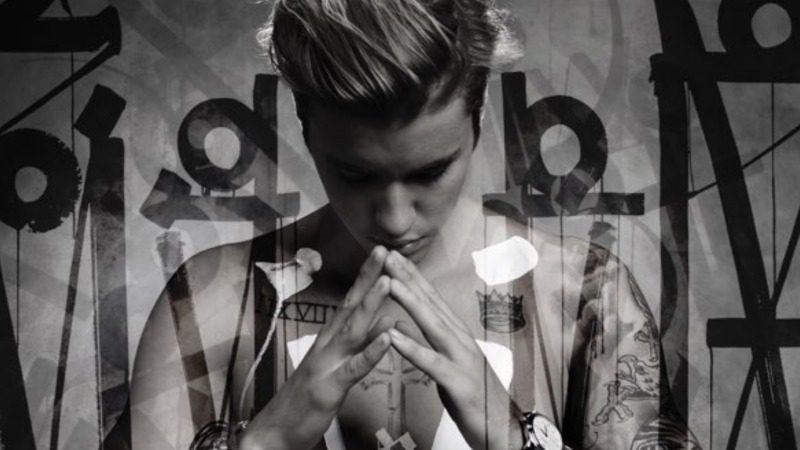

2015 was the most awkward year in pop’s late-Obama-era moral reckoning, when male artists’ attempts to function in a new world of moral accountability and altruistic misandry had turned into a sort of circus. I wonder if future critics will understand how deeply this post-”Blurred Lines” impulse went, brewing into the climate that produced pop’s most auspicious album-as-apology, Justin Bieber’s Purpose.

The story of Bieber’s fall from grace was even more exhausting to live through than it was to tell: the egging of neighbors’ houses, the wrapping cars around trees, the creepy entourage of enablers and celebrity Christians he was hanging with. The world expected a child-star flameout, and his struggle to balance his public life with PR scrutiny has never really gone away even through multiple comebacks and unexpected late-game wins; getting famous at that early an age frankly fucks with your brain. But by lassoing himself to the EDM-pop sound that producers like Diplo and Skrillex were brewing up, he was able to give his pop career a new lease on life while shedding the teenybopper image of his past.

It’s strange in retrospect that Purpose is now essentially early Bieber. Still to come were the failed pivot to straight-up bathtub-&-roses R&B that produced the monstrosity “Yummy,” not to mention his subsequent reinvention as a reliable Christian husband and nuclear-family proponent who will run to the altar like a track star, or his recent linkage with Dijon and his already Bieber-like sideman Mk.gee.

At the time Purpose came out I was impressed by Bieber’s poise—the icy arch-diva manner that betrayed the androgyny he showed in his early years, back when he was the target of residual Bush-era clenched-assholism, even in spite of his attempt to present himself as a model of frat-boy perfection. “I’m not made out of steel,” he sings on “I’ll Show You”; the line works because it sounds like he is. Ten years later, I hear Bieber trying to find a way to break through in a world where the public response to transgression was fierce and immediate, and to be a white Canadian R&B singer with a record of shitty and entitled behavior (not least that chainsaw joke) was a bad position in which to find yourself. Confronted with this strange new era, he’s like a swallow knocking his head against the walls of an attic in terror.

The nice thing about pop artists with a mean streak and something to prove is they tend to turn the knob up on their own music. You can hear this impulse on Michael Jackson’s Dangerous, released back when the worst of his scandals was buying the Elephant Man’s bones; to counter his haters, he climbed into Teddy Riley’s beats and wielded them like a mech to clobber anyone who dared to throw vitriol towards such a sensitive soul. (I’d like to imagine Bieber’s popcorn movie of choice around this time was Pacific Rim, the emo Guillermo Del Toro epic where the feelings of the pilots came into violent conflict with their assigned monster-bashing duties.)

What’s weird about Purpose, though, is it’s simultaneously a heel turn and a mea culpa. You get acres of Bieber saying things like “I’m working on a better me” and “my reputation is on the line,” and then you get “Love Yourself,” one of the most brutal songs to chart since Hall & Oates sang about the Rich Girl as if she was Homo Erectus. How did that sap Ed Sheeran write this? He must have a poison pen locked in his bottom drawer. Lines like “I’m so caught up in my job” fit with the apologetic tenor of the album, but when Bieber lambasts his target for talking shit about his friends (“the problem was with you and not them”), we remember the kind of weirdos Bieber was hanging out with in the day and concede maybe the star hasn’t learned so much after all. Sheeran thought it was too mean for his own music, but it fits great here, a crack in the façade that ends up feeling more honest than all the PR shit.

The perfect version of the album that exists in my mind leans into that meanness, but there’s no way anyone could’ve released something like that in 2015, where public penance was a spectator sport and admitting to your faults was no longer especially endearing. The same perfect version leans a little further into its sonic extremities. Bieber had the backing of Skrillex and Diplo, who included his admittedly flawless vocals on “Where Are Ü Now” from their Jack Ü collab. The drum hits sound huge, the dembow beats lope along with precision-engineered grace, the trap beats are as gleaming as anything released during that mid-2010s window when production techniques from Atlanta reached an apex of gothic grandeur. But in 2025, when this sound is nostalgia bait and underground upstarts like Frost Children and Ninajirachi have lit a cherry bomb under it, it sounds a little weak. It’s especially funny to hear the dembow beat on “Sorry” in context of the late-2010s stateside reggaeton revolution, which Bieber had a part in launching as a guest on Luis Fonsi’s “Despacito” remix.

Most crucially, that perfect version of Purpose caps at nine songs, the same as Thriller. Streaming was just starting to reshape the form and content of major pop albums, which would lead to major albums being polarized either between endless slogs meant to goose streaming figures (Migos’ Culture series, Bieber’s own Swag II) or short sharp shocks calibrated for the attention span of the terminally online (Kanye’s Wyoming series). Albums still mostly followed the CD-era blueprint at the time, clocking in at an hourish, more concerned with the customer feeling like they got their money’s worth than with having a coherent arc; you ended up with endless telephone interludes, shoehorned collaborations, dull ballads, a general deadness.

Purpose is no exception. This isn’t an album anyone is going to be pillaging for its deep cuts, and its three singles are sequenced next to each other in a perfect triad—ballsy sequencing if the album cuts left you with much to discover, less so when the singles are obviously the best thing here. The Justin Bieber catalogue remains spotty and has yet to produce a classic in the vein of FutureSex/LoveSounds or Lemonade. His current era is probably his most consistent, and though the MLK sample on 2021’s Justice led to yet another PR disaster, it’s nearly as good as the two Swag albums he made in conjunction with the Dijon stable this year.

Purpose is probably in the lower middle in my personal ranking of his catalogue, but as a relic of a time when the hedonistic EDM era and the public-accountability era muddied waters, it’s flawless. These days, the celebrity culture has shifted towards celebrating trashiness as it did in the 2000s, which along with the termination of his recent alliance with mogul Scooter Braun suggests it’s wiser now for him to parlay his PR disasters into memes (“standing on business”) than to make like Pee-Wee and play the humble citizen. Ten years on, Purpose stands as a reminder of just how much the mid-2010s were like a kid at prom, agonizing about whether or not to put his hand on his date’s shoulder, as the photographer immortalizes a moment the poor kid will wince to look upon later.

Daniel Bromfield is a writer, editor and musician from San Francisco, CA. He currently works as Calendar Editor at the Marin Independent Journal and is a prolific freelancer, with bylines at Pitchfork, Atlas Obscura, Resident Advisor and local media in the Bay Area. He runs the popular @RegionalUSFood Twitter account, highlighting obscure dishes from across the US. Find him on Twitter at @bromf3.