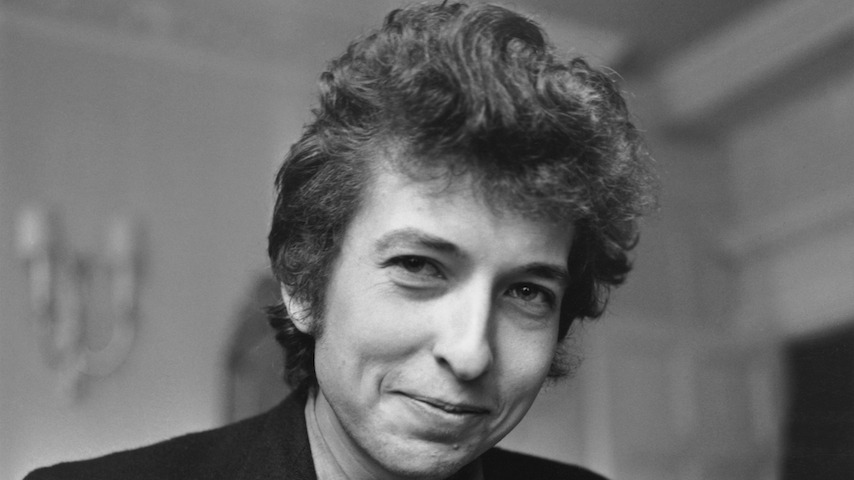

This Friday, Bob Dylan’s 39th studio album, Rough and Rowdy Ways, will be released around the world. To celebrate the new album and refresh ourselves in preparation, here is a condensed breakdown of Bob Dylan’s prolific life, music and legacy. Read Paste’s review of Rough and Rowdy Ways right here.

1941-1962

Born Robert Zimmerman in the port city of Duluth, Minn., Bob Dylan grew up listening to the popular rock and country music of the era, such as Elvis Presley, Little Richard and Hank Williams. Yet, it wasn’t until he graduated high school, started school at the University of Minnesota and began performing with regional star Bobby Vee that Dylan was first truly exposed to the folk music that would profoundly shape him as an artist. After immersing himself in contemporary folk music during his first year at college, Dylan abandoned his studies and hitchhiked his way to New Jersey to meet his artistic idol, Woody Guthrie. A renowned folk musician and beat poet, Guthrie had been hospitalized for Huntington’s Disease by the point at which an enamored Dylan paid him a visit. “You could listen to his songs and actually learn how to live,” said Dylan of Guthrie’s music in the 2005 documentary No Direction Home. Trading his electric guitar for an acoustic and relocating to New York City directly thereafter, the Robert Zimmerman of the Iron Range was left behind: In his place was Bob Dylan, folk disciple and the soon-to-be voice of a generation.

When Dylan first arrived in Greenwich village, playing sets in tiny run-down bars filled with beat poets and cigarette smoke, his unique rendering of western-folk classics immediately began to attract attention.

His first album, the self titled Bob Dylan, recorded in 1962 and released through Columbia Records, barely sold 5,000 copies in its first year. Yet, this album would both wedge Dylan’s foot into the industry’s door and allow him to begin crafting a personal mythology for the first time. In Bob Dylan, you can hear as he begins to experiment with his emblematic harmonica, twisting old folk songs into shiny new tunes and bringing together his disparate influences into his own unique sound. Fun fact: Dylan actually stole this “House of the Rising Sun” arrangement from fellow Village musician Dave Van Ronk, who, following the album’s release, was unable to perform his own arrangement, as people thought he had stolen it from Dylan.

1963-1964

In 1963, the United States was in the throes of social turmoil. As the civil rights movement continued to unfold and nuclear tensions with the Soviet Union escalated, Dylan released his second album, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan. Encouraged by his then-girlfriend Suze Rotolo, Dylan had begun trying his hand at writing and performing protest songs informed by the civil rights movement, the nascent anti-war movement and general tumult roiling America. A treasure trove of protest songs, folk ballads and love letters,The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan established Dylan both as a musician and political icon, tackling themes from the ongoing civil rights movement and institutional racism to commentary on America’s foreign relations. By mid-1963, after performing alongside Joan Baez at the March on Washington, Dylan had become more than a singer-songwriter: He had become an icon of social change.

Released in 1964, his third album, The Times They Are A-Changin’, was an intricately stitched quilt of social commentary and blistering critique of societal injustices, held together by Dylan’s reflective poeticism. The album’s sixth track, “Only a Pawn in Their Game,” perhaps best embodied the revolutionary spirit that informed Dylan’s work during this era. “A bullet from the back of a bush took Medgar Evers’ blood…Two eyes took the aim / Behind a man’s brain / But he can’t be blamed / He’s only a pawn in their game,” Dylan sings in the song’s first verse, referring to the assassination of the civil rights activist Medgar Evers and illuminating the realities of systematic racism in America.

Yet, Dylan resisted the categorization of his music as belonging to any particular genre; he didn’t enjoy being compartmentalized as an artist—as was detailed in Robert Shelton’s No Direction Home: The Life and Music of Bob Dylan—and even less so as a human. By the release of his next album, Dylan had therefore turned inwards once again for his thematic material and inspiration.

1965-1973

In the summer of 1965, while performing a set at the Newport Folk Festival, Dylan was famously booed off stage for the first time. Amid accusations of selling out, Dylan had begun incorporating electric equipment into his sets, much to his fans’ displeasure (a displeasure quite arguably rooted less in objective musical criticism than in a sense of betrayal). His subsequent 1966 tour circuit featured both his older acoustic works and his more recent electric ones, placing Dylan in the center of a heated controversy over his motives and authenticity. Although fans at the time felt as if he had betrayed his legacy by “selling out and plugging in,” Dylan’s first fully electric album, Highway 61 Revisited and his follow-up (and most famously electric) album, Blonde On Blonde, were hugely influential points in folk-rock music, pushing the genre into uncharted territory.

Dylan produced so much brilliant music during this period of time that it is truly difficult to point to one or two songs as representations of the internal and external change that occurred over Dylan’s electric years, from the first time he dipped his toe into rock on Bring It All Back Home to his lush, electric smash hit “Like A Rolling Stone.” Hear Dylan perform “Like A Rolling Stone” with The Band live in 1974:

1974-1978

For artists, heartbreak often inhabits the space between personal pain and creative productivity. Although the process itself is uncomfortable, as it is for everyone, the experience of heartbreak often leads to an artist’s best work. This was undoubtedly the case for Dylan in the years following the disintegration of his marriage with Sara Lownds in 1977. Widely known as “the breakup album,” (and one of the best breakup albums ever) Dylan’s 1975 record Blood On the Tracks is one of his greatest works, as well as arguably his last album fully rooted in the folk tradition (at least for a while). Written after returning from his 1974 tour and becoming estranged from his wife, the album was influenced by a lecture class Dylan attended taught by Norman Raeben, a New York-based painter who advocated for intuition over conceptualization when creating art.

The album opens with “Tangled Up in Blue,” a rich and vivid time-bending fable told by weaving between the first and third person. Dylan said that “(the song) took 10 years to live and two years to write.” The album also contains some of Dylan’s softest and most delicate work, including tracks like “Shelter From the Storm” and “Buckets of Rain” which contemplated his crumbling relationship with Lownds over acoustic guitar and harmonica.

1978-1981

After releasing his 1975 record, Dylan embarked on a series of tours spanning four years, backed by an enormous ensemble. It was during this time that Dylan’s religious explorations dominated his music. Immersing himself in gospel music and scripture, Dylan completed his conversion from Jewish to Evangelical Christian in merely a matter of months in the late 1970s after attending three months of Bible School, as was detailed in Jeremy Roberts’ book Bob Dylan: Voice of a Generation. This sudden transformation resulted in three evangelical albums over the next few years: Slow Train Coming, Saved and Shot Of Love. When on tour over the next few years, Dylan refused to play his old secular works, and replaced his on-stage banter with recitations of Bible passages, musings on the apocalypse and bits of scripture.

Although by 1982 Dylan had mostly returned to writing and performing secular works, his years as a proselytizer had cost him a significant portion of his fanbase. Yet, Slow Train Coming was still named one of the 100 greatest albums in Christian music by CCM, and made it to the top of many a Billboard chart. If that’s your cup of tea, listen to “Gotta Serve Somebody” from Slow Train Coming below.

1982-1987

While the ’60s and ’70s gave rise to some of Dylan’s greatest works, the ’80s gave rise to some of his most underwhelming. To fans of both his acoustic and electric periods, the years spent rebuilding his legacy from 1982-1987 were marked largely by a series of disappointing musical experiments. Out of his born-again phase but having lost many of his fans through radical messaging, Dylan rambled through much of the ’80s. In this era, his songwriting felt aimless and lost in its own design, the tangible manifestation of a man searching for his place, both musically and personally. Afloat in a sea of expectations and hazy creative impulses, Dylan sounded profoundly lost. Yet, a closer look at Dylan’s output from the ’80s reveals a handful of hidden gems. Watch Dylan perform his single “Dark Eyes,” a track off his 1985 album Empire Burlesque, live with Patti Smith below.

1988 – Present Day

Climbing out of the fog of the ’80s was no easy task, but as years turned to decades, Dylan gradually began to reimagine his creative process and reshape the way he engaged with his audience as a performer. Embarking upon his “never ending tour” in 1988—a tour which has been active for more than 30 years with more than a whopping 3,000 performances—Dylan slowly began to re-harness his creative energy, producing some of the greatest works from the second half of his career such as his Grammy-winning 1997 album Time Out Of Mind, his 2001 album Love And Theft and his lyrically stunning 2012 album Tempest.

In 2016, the Nobel Committee for Literature at the Swedish Academy announced Dylan as that year’s laureate, marking the first time a musician had won the Nobel Prize for Literature (and sparking a subsequent impassioned debate whether lyrics can be severed from music and consumed as a separate form of art). Now, eight years after his last album of original material and four years after winning the Nobel Prize, Bob Dylan is set to return this Friday with an album, Rough and Rowdy Ways. The album will include the 17-minute (!) spoken-word ballad released earlier this year, “Murder Most Foul,” on which Dylan remembers the ’60s, JFK’s assassination and his contemporaries at the time.

What is it then about Dylan, an artist who has spent his career resisting definition and rejecting easy classification, that compels us to continue to try to define and classify him? Perhaps it’s his reluctance to embrace main-stream approval, as reflected—delightfully, to some, and maddeningly, to others—in his failure to show proper gratitude for the award of the Nobel Prize.

Yet, if we know anything about Bob Dylan, we should know by now to at least try and let go of expectation. It is in that manner that we best prepare ourselves to meet the artist on the only ground he has ever walked: his own.

Revisit a 1988 Bob Dylan concert from the Paste vault below: