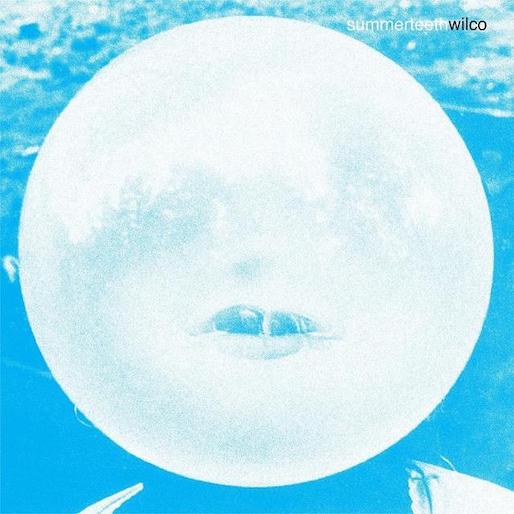

For all that musicians have spilled their guts about the pitfalls of the rock and roll lifestyle—the usual drugs, excesses, etc.—it’s relatively rare to get a window into the toll that success takes on families. In that regard, Wilco’s third album Summerteeth doesn’t offer much, if anything, by way of explicit insights, but it does stand as an affecting example of the anguish that can creep into an artist’s work when that work forces a kind of functional estrangement from home. As Wilco’s star ascended on the momentum of their 1996 double-album breakout Being There, bandleader Jeff Tweedy, a new father at the time, struggled to cope with having to spend the majority of 1997 away from his spouse and infant son. “When you come home,” he told Greg Kot in Kot’s 2004 Wilco biography Learning How to Die, “it’s hard not to feel like you’re in somebody else’s house, [and it’s hard] to make that transition and feel integrated as a human being. Being home and trying to get back in touch with your real self is almost impossible in the time span [in] which you have to do it, which is usually only a few days.”

It was in this crucible of mounting fame, homesickness, anxiety and well-documented substance abuse that Wilco created Summerteeth, an album marked by, among other things, its beguiling contrast between disquieting lyrics and a mostly sunny musical disposition. Right off the bat, before Tweedy even sings his first word, musical bells chime along with the main hook on the opening track “Can’t Stand It,” setting the table with a similar kind of evocation of joy that one hears in holiday commercials. Even after years’ worth of listens where you know exactly what’s coming, “Can’t Stand It” has a way of disarming you so that you don’t register what Tweedy is actually singing, which is that “you get so low / struggle to find your skin.”

The darkest album in Wilco’s catalog by far, Summerteeth does wear its despondence more nakedly on its sleeve in certain spots. To varying degrees, eventual Wilco live staples like “Via Chicago” and “She’s A Jar” harbor chilling overtones of violence that align more closely with the delicate musical bandages the band applied to them. But the relational discord at the wounded heart of Summerteeth never actually reflects Tweedy’s domestic life in a literal, confessional sense. Increasingly influenced by modern literature, Tweedy began experimenting with a lyrical technique where disconnected images gelled into a picture, but a picture that was vague enough for Tweedy himself to remain unsure of what a given song was trying to communicate.

Nevertheless, the album’s overall outlook, which Tweedy described to Kot as “morbidly depressed,” intimates the inner turmoil Tweedy and some of his bandmates at the time were grappling with when he penned lines like “I dreamed about killing you again last night / and it felt alright to me.” As then-drummer Ken Coomer told Kot in the same book, “He was a crying wreck recording some of those songs. There was a lot of self-medicating going on. He was pumping painkillers and going through a horrific time. His songwriting got more personal, introspective. It was great, but holy hell what a price to pay. Sometimes I wondered how ambiguous his lyrics were, and I’d see things pop up and realize it was more personal. You put a bunch of grown men in this giant tube that travels across the country, you create your own moral universe, and you live by your own rules. As good a person as I think I am, I ruined some relationships that way. I think we all did.”

For the better part of the last 20 years, radical change from album to album has become synonymous with Wilco’s brand. Leading up to 1999, however, Wilco were still widely viewed as alt-country/no depression standard bearers, a designation they had come to chafe against. “There was a real suspicion of roots music and nostalgia in the band at the time,” Tweedy wrote in his 2018 memoir Let’s Go (So We Can Get Back). “The way some bands were working so hard to come across as authentic by adapting their image to some backwoods chic was really making us skeptical about taking inspiration from looking back[wards] musically. Our heads were pointed much more in the direction of pushing ourselves into some sort of new sonic pop territory, anything that felt unexplored by us. Summerteeth was partly a reaction to how defined the band had become by the alt-country tag.”

Just as significantly, the album also captures the point where Tweedy’s self-described “symbiotic” creative partnership with late lead guitarist, multi-instrumentalist and in-house producer of sorts Jay Bennett reached its apex. Friction between Bennett and Tweedy would later sink their relationship, but for Summerteeth the pair fed off one another, both getting swept away as they worked together to lavish the songs with overdubs. “Jay Bennett and I,” Tweedy added in his memoir, “were probably at our most compatible in terms of our creative relationship during the making of Summerteeth. In hindsight, it was a pretty unhealthy environment.”

Unhealthy, perhaps, but fruitful to say the least. Though Bennett’s studio acumen and taste for grandiose, Pet Sounds-styled layering somewhat marginalized Coomer and bassist John Stirratt (who initially found the finished album “too dense, too claustrophobic”), Summerteeth would never have developed into the album it became without Bennett’s willingness to abet Tweedy in his growing desire to take his song ideas out on a limb, come what may. If Being There captured Tweedy starting to stretch past the parameters of conventional song structure, Summerteeth stepped into a surrealist realm where, say, two wildly different takes of the same song could blend together to create a dreamlike suspension of physics, musically speaking.

With Tweedy and Bennett mutually amplifying each other’s sense of freedom, Summerteeth would come to encompass bluesy roots rock, country and power pop, all inflected with a newfound soulfulness while simultaneously undercut with an experimental streak informed by post-punk and art rock. Though they intentionally coated the music with a sheen of bright polish, they also weren’t opposed to making the audience work. Not as lengthy but arguably more far-reaching than Being There, the numerous momentum shifts in Summerteeth’s running order take time to digest. And it’s telling that Tweedy and Bennett wanted the album to lead off with the somber, downtempo twang of “She’s A Jar” until Reprise Records intervened.

That said, Bennett’s work on the piano, along with an arsenal of keyboards, decorates the songs like garland streamers hung in every direction (though rather tastefully so). As just one example, Bennett supplies one of the main hooks for “I’m Always In Love” with a wailing synth reminiscent of the most iconic, hummable lines by Greg Hawkes of The Cars. Bennett’s frothy splashes of organ subtly support the buoyant feeling of elation the whole band establishes as the song ambles along in what might best be described as a leisurely gallop—also supplied by Bennett on drums. Finally, Bennett’s piano chords underscore the poignance hiding in Tweedy’s original melody.

As various documentary and TV clips from that period show, Tweedy and Bennett made some of their most direct, heartfelt musical statements with nothing more than acoustic guitar, vocals and piano. Unfortunately, the two dozen recordings of works in progress included in the new deluxe Summerteeth reissue don’t showcase their work as a duo, but this expanded edition does include 11 lo-fi cassette recordings of Tweedy sketching songs out on an acoustic guitar. If Tweedy’s 2018/19 solo albums Warm and Warmer appeared to come from an artist who’s mastered songcraft after decades of effort, these newly unearthed Summerteeth-era sketches reveal that Tweedy’s singular gift was there at least as far back as the late ‘90s.

Fans of the original album may find themselves in shock at just how much Tweedy’s raw tapes—basically glorified notes to himself—manage to convey the essential spirit of the songs, even when stripped to the barest flint of bone. The sketch of “I’m Always In Love,” for example, allows listeners to re-imagine the song rolling across the Great Plains in the 1800s, strummed by a pioneer heading west on the “big-wheeled wagon” that features in the lyrics. In the sketch of “Candyfloss,” one hears the possibilities for how the song could have evolved into something much closer to the maximalist abstraction that unifies the rest of the album, as opposed to its nostalgic, bubblegum-y final form, which Tweedy deemed so out-of-step with the album proper that he consigned it to hidden-track status.

On “All I Need,” an embryonic version of “Shot in the Arm,” Tweedy’s throat sounds especially worn from cigarette smoke as he ad-libs references to constipation and the children’s book The Very Hungry Caterpillar. “I’ll Sing It,” meanwhile, doesn’t sound all that far off from the form it took 15 years later on Sukierae, the 2014 duo album he released with his son Spencer under the name Tweedy. The aching “No Hurry” presages the bittersweet chord progression of “I Am Trying to Break Your Heart,” a would-be hint of the pivotal turning point to come just one album later. Alas, “No Hurry” never made it to the public in finished form, but in this version Tweedy outdoes Guided By Voices leader Robert Pollard in the thrift department, achieving wholeness out of the most spare ingredients.

As epic and soul-stirring as anything Tweedy has ever put out, “No Hurry” tantalizes the imagination with hints of what it would have become when subjected to a full Summerteeth-style arrangement, but it stands entirely, assuredly on its own. All too often, these types of warts-and-all artifacts retrieved from an artist’s shoebox don’t make for a coherent listening experience, but these solo Tweedy tracks add dimension and shading to such a degree that they’re almost as rewarding as finding a lost, finished album—arguably as revelatory and radiant as Willie Nelson’s archival demos released in 2003 as Crazy: The Demo Sessions. Likewise, the never-released full-band outtake “Viking Dan” sees Wilco marshalling the tempestuous power of Zeppelin’s “Trampled Under Foot” and marrying it to the slinky funk of The Stones’ “Miss You.” Throughout, Coomer—a less flexible but more innately grooving player more steeped in country and rock than his eventual replacement Glenn Kotche—shows why the band have operated more from the head than the gut since his departure.

On the other hand, where the complete bonus concert on 2017’s deluxe Being There reissue captured an almost feral live act that could burn the house down in a blaze of hard-driving roots rock, the 1999 live material included here gives us a snapshot of a lethargic group struggling to breathe life into their songs. One of the most rousing moments occurs when an audience member shouts “You guys rock!” and Tweedy shouts back, “No we don’t!” Even with the addition of multi-instrumentalist Leroy Bach (who, inexcusably, isn’t credited in the liner notes), this incarnation of Wilco doesn’t come anywhere close to recreating the fullness, color or grace of the Summerteeth studio arrangements.

Moreover, the vinyl and CD packages come with different performances, each available only in that format, which inflicts extra expense on people who have paid for this album once already. And one final caveat: The remastering job alters the music’s sonic character fairly dramatically. Sure, the new master highlights a slew of subtleties that weren’t evident until now, but it’s enough of a trade-off that it would have been nice to include the definitive version, as well.

Summerteeth is precisely the kind of challenging, detail-rich, time- and investment-rewarding work that warrants the deluxe treatment. Two decades later, the album’s well of mysteries still entices and, in some ways, continues to elude understanding. The more scrutiny you give these seemingly straightforward songs, the more mysterious they become, even as they grow more familiar. That said, while this expanded edition certainly helps provide context, opening new windows on a classic, long-inactive lineup of a band that was oozing with inspiration and still had something to prove, even listeners above the casual-fan threshold should exercise caution before taking the plunge a second time around.

Saby Reyes-Kulkarni is a longtime contributor at Paste. You can find him on Twitter.

Revisit a Being There-era Wilco performance below via the Paste vault.